Service Strategy

6. Strategy & Organization

| 'I was in a warm bed, and suddenly I'm part of a plan.' Woody Allen in Shadows and Fog "

|

| Organizations

Organizations are goal-directed, boundary maintaining and socially constructed systems of human activity. Organizations are designed and built for a purpose. These goals drive the behaviours of an organization's many agents who dynamically interact with each other. The many interactions produce emergent macro-level patterns of organizational behaviour. IT organizations are complex systems embedded within the larger complex system of its business, customers and industry.

The transaction costs principle is a simple and yet

powerful means for explaining organizations. It argues that, in certain circumstances, organizations are more efficient mechanisms for cooperation than contracting or sourcing. IT organizations are subject to transaction costs. They must search for, negotiate, monitor, coordinate and govern resources in order to produce services. As people come together in an organization, they must learn what to do and how to work with others to perform. If this cooperation is done ineffectively, transaction costs rise. The better the organization manages its transaction costs, the better it justifies its existence. Further, certain risks are better mitigated through organizations than through contracts:

- Incomplete contracts - no contract can ever cover every possible contingency. The greater and more complex the cooperation needed with external contractors, the greater the possibility of an incomplete contract.

- The hold-up problem - services often require investments in specific assets such as infrastructure or facilities. The problem of incomplete contracts implies that there is always a possibility that contracts will unravel. Contractors are then stuck with these hard-toreverse assets and may then withhold access as they seek better terms.

- Change endurance - organizations create structures that outlive the participation of their agents. These cooperative structures allow an organization to strive for complex strategies that may require years to enact.

Collective learning - much like individuals, organizations are capable of learning." Despite changes in individuals, organizations act as a stabilizing and collective storehouse for knowledge while in pursuit of their goals.

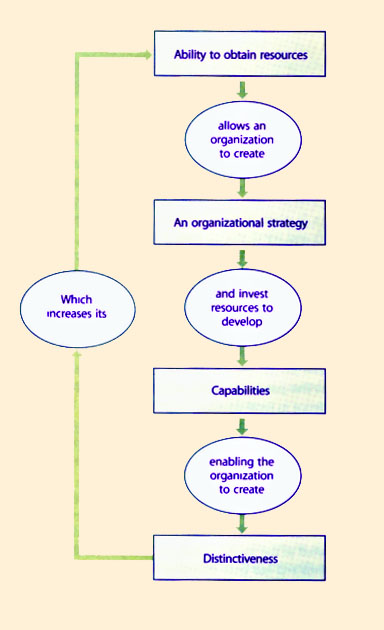

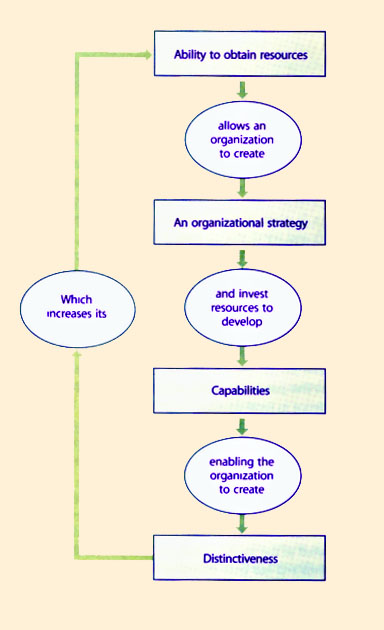

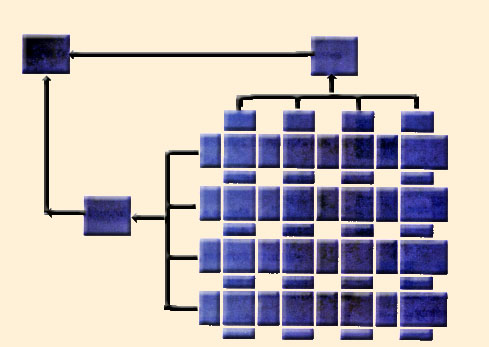

Adequate scarce resources, a well-considered strategy and distinctiveness allow an organization to provide superior performance versus competing alternatives, in turn justifying the acquisition of still more scarce resources. This virtuous cycle is illustrated in Figure 6.1.

|

| | Figure 6.1 Organizational value creation cycle< |

|

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

6.1 Organizational Development

When senior managers adopt a service management orientation, they are adopting a vision for the organization. Such a vision provides a model toward which staff can work. Organizational change, however, is not instantaneous. Senior managers often make the mistake of thinking that announcing the organizational change is the same as making it happen.

There is no one best way to organize. Elements of an organizational design, such as scale, scope and structure, are highly dependent on strategic objectives. Over time, an organization will likely outgrow its design. There is the underlying problem of structural fit. Certain organizational designs fit while others do not. The design challenge is to identify and select among often distinct choices. Thus the problem becomes much more solvable when there is an understanding of the factors that generate fit and the trade-offs involved, such as control and coordination.

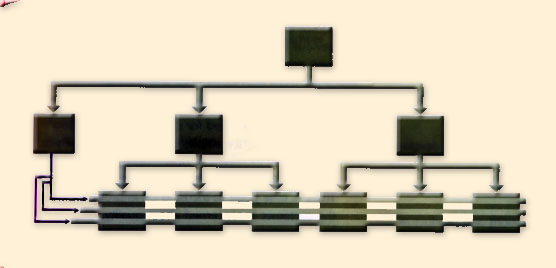

When the organization performs well, the structure tends to drift towards a decentralized model where local managers possess greater autonomy (Figure 6.2). When problems persist, the tendency is to shift to a centralized model. This pendulum swing represents a lack of confidence in local decision making. Despite the extreme difficulties, there is a persistent belief that an organization is controlled from the top. But giving orders is not the same as being in control. There are no guarantees, however, that local managers will appreciate the impact of their decisions on the larger organization. Their decisions can be short-term and short-sighted. This wavering between centralized and decentralized management is attributed as the source of long-term organizational problems and has been described as, 'the illusion of being

in control'. How then, does an organization decide how to best manage its current organization and where to land along the design spectrum?

Organizational development

1 The global CIO of this Fortune 50 automotive company built an IT organization in an unusual manner. He hires divisional CIOs to correspond to business divisions: North America, Europe, AsiaPacific, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and finance. At the same time, he hires process information officers (PlOs) to work horizontally in different specialities across all divisions around the world: product development, supply chain management, production, customer experience and business services (HR, legal and so on).

2 The IT organization for one of the most popular sports leagues in North America flourishes under a culture of speed and entrepreneurship. Sunday game results and media events often dictate service activities with short time frames. Service processes are minimally structured, with room for improvisation and adaptation.

What are these organizational structures called?R

|

The process for major organizational change involves many events and can be a matter of years rather than months. Leading this change is difficult and should not be

reduced to quick or simple fixes. The ability to lead this change is an important competence for senior executives and managers. Understanding when a service strategy is too complicated and rigid is as important as any support process.

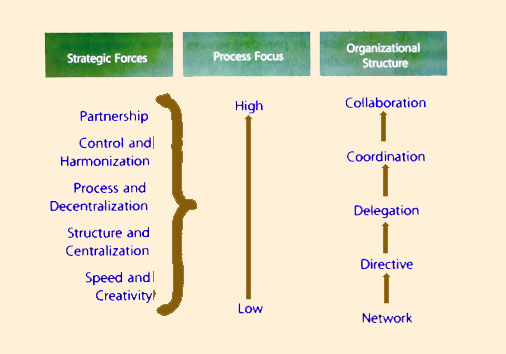

Outside forces greatly influence an organization's service strategy, which in turn determines the organizational structure. Where the lines are drawn depends on what the organization is attempting to accomplish. A service strategy then becomes an implicit blueprint for an organization's design, shaping scale and scope. Scale refers to size. Scope refers not only to the broadness of service offerings - it also describes the range of activities the organization performs. When an organization decides on a make-or-buy strategy, for example, it is determining the scope of its activities. The trade-offs are control versus coordination.

An organization's age and size affect its structure. As the organization grows and matures, changes in roles and relationships must be made or problems will arise. This is particularly important for organizations adopting a service orientation, as pressures for efficiency and discipline inevitably lead to greater formalization and complexity. The risk over time is that the organization becomes too bureaucratic and rigid.

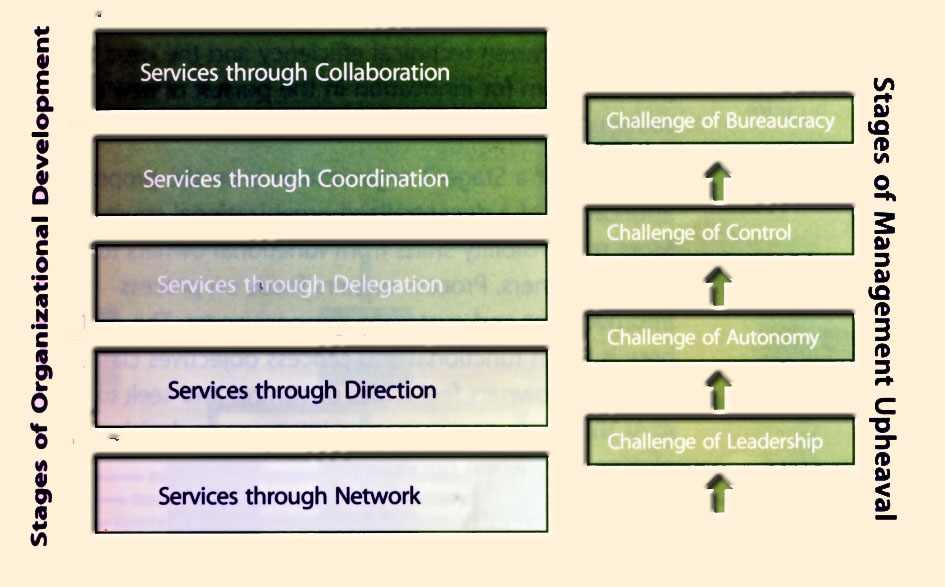

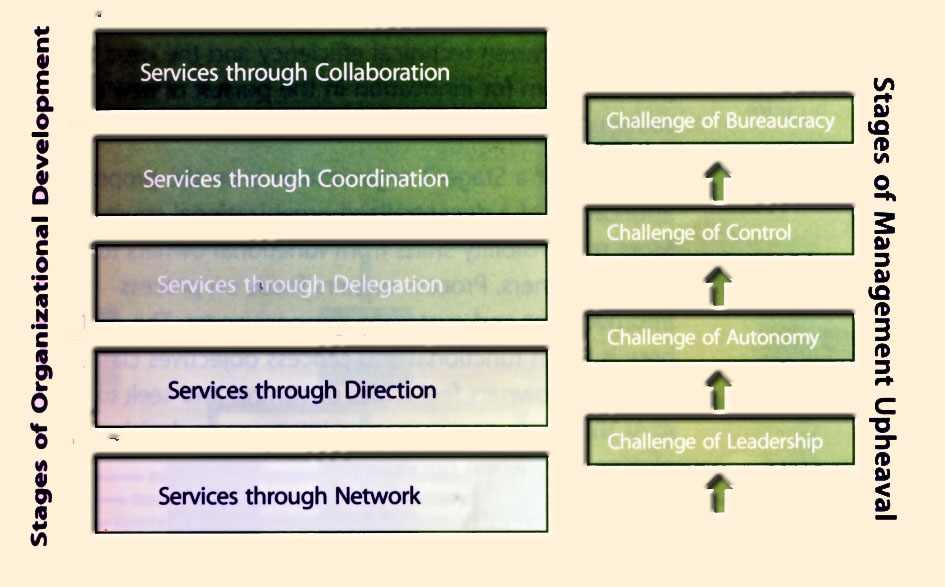

Most IT organizations tend to grow for prolonged periods without severe setbacks. The term evolution describes the quieter periods while the term revolution describes the upheaval of management practices. Organizations are

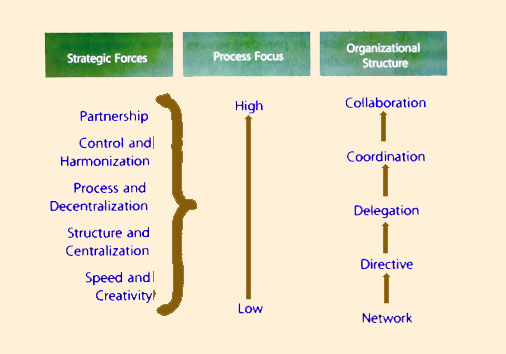

generally characterized by a dominant management style: Network, Directive, Delegative, Coordinated or Collaborative (Figure 6.3). Each style serves the needs of the organization for a period of time. As service requirements evolve, the organization encounters a dominant management challenge that must be resolved before growth can continue. The organization can no longer address its service challenge with its current management style. Nor can it be successful by retreating to a previous style - it must move ahead.

|

| Figure 6.3 Stages of Organizational Development |

6.1.1.Stage 1: Network

|

The focus of a Stage-1 organization is on the rapid, informal and ad hoc delivery of services. The organization is highly technology-oriented, perhaps entrepreneurial, and is reluctant to adopt formal structures. Innovation and entrepreneurship are important organizational values. The organization learns which processes and services work and adjusts accordingly. The organization believes that informal structures are far better suited to the resources required to deliver services. Past successes reinforce this belief. As the service demands grow, this model is not sustainable. It requires great local knowledge and intense dedication on the part of the staff. Conflict is created as staff resist the creation of service structures.

As the organization grows and the need for efficient resources increases, leaders are confronted with the task of having to manage an organization. This is a very different skill from technology and entrepreneurship and often a task for which leaders find themselves ill prepared.

A common structure in this stage is called a network (Figure 6.4). A network structure is a cluster whose actions are coordinated by agreements rather than through a formal hierarchy of authority. The members work closely together to complement each other's activities. The goal of the organization is to share its skills with the customer in order to allow them to become more efficient, reduce costs or improve quality.

- It avoids the high bureaucratic costs of operating a complex organizational structure

- The organization can be kept flat with fewer managers required

- The organization can quickly adapt or alter its structure.

- The practical disadvantages of a network structure:

- Managers must ensure the activities of the staff are integrated

- The coordination problems are significant

- There are difficulties in externally sourcing functional activities.

| Guidance: to grow past this challenge requires a significant change in leadership style. While this is accomplished through a variety of human performance techniques and methods, the desired outcome is a cadre of strong managers skilled and experienced in service management structures. Their influence and business focus are essential for moving to the next stage.

|

| | Figure 6.4 Services through network |

| |

6.1.2 Stage-2: Directive

|

The Stage-1 crisis of leadership ends with a strong management team. They take responsibility for directing strategy and direct low-level managers to assume functional responsibilities (Figure 6.5).

The focus of a Stage-2 organization is on hierarchical structures that separate functional activities. Communication is more formal and basic processes are in place. Although effort and energy are diligently applied to services, they are likely to be inefficient. Functional specialists are frequently faced with the difficult decision of whether to follow the process or take the initiative on their own.

A crisis of autonomy arises because the centralization limits decision making and the freedom to experiment or innovate. Entrepreneurial motivation is degraded. For example, high-level approval is needed to start new projects, while successful performance at the lower levels goes unnoticed or unrewarded. Staff become frustrated with their lack of autonomy. By not solving this crisis, the organization limits its ability to grow and prosper.

| Guidance: to grow past this challenge requires a shift to greater delegation. Responsibility for service processes should be driven lower in the organization, allowing process owners to be responsible for lower-level decision making and service accountability.

|

|

| | Figure 6.5 Services through direction |

|

6.1.3 Stage-3: Delegation

|

The Stage-2 crisis ends with the delegation of authority to lower-level managers, linking their increased control to a corresponding reward structure (Figure 6.6). Growth through delegation allows the organization to strike a balance between technical efficiency and the need to provide room for innovation in the pursuit of new means to reduce costs or improve services.

The focus of a Stage-3 organization is on the proper application of a decentralized organizational structure. More responsibility shifts from functional owners to process owners. Process owners focus on process improvement and customer responsiveness. The challenge here is when functional and process objectives clash. Functional owners feel a loss of control and seek to regain it. At this stage, top managers intervene in decision making only when necessary.

| Guidance: Rather than the frequent reaction of returning to a functionally centralized model, the recommended approach is to enhance the organization's coordination techniques and solutions. The most common approach is through formal systems and programmes. There are occasions when an organization attempts to resolve the coordination challenge by centralizing on a process, rather than functional model. Rather than creating a white space between functions, this leads to white space between processes. In other words, a pure process model is as problematic as a purely functional organizational model. A balance should be sought or the organization will revert back to a crisis of autonomy.

|

|

| | Figure 6.6 Services through delegation |

|

6.1.4 Stage-4: Coordination

|

The focus of a Stage-4 organization is on the use of formal systems in achieving greater coordination (Figure 6.7).

Senior executives acknowledge the criticality of these systems and take responsibility for success of the solutions. The solutions lead to planned service management structures that are intensely reviewed and continually improved. Each service is treated as a carefully nurtured and monitored investment. Technical functions remain centralized while service management processes are decentralized.

The challenge here is the ability to respond to business needs in an agile manner. The business often adopts a perception that IT, despite its service orientation, has become too bureaucratic and rigid. While the linkages to the business may be well understood, innovation is dampened and service procedures have taken precedence over business agility.

|

| | Figure 6.7 Services through coordination |

|

6.1.5 Stage-5: Collaboration

|

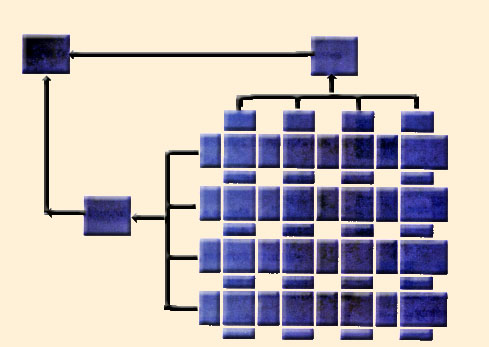

The focus of a Stage-5 organization is on stronger collaboration with the business (Figure 6.8). Relationship management is more flexible, while managers are highly skilled in teamwork and conflict resolution. The organization responds to changes in business conditions and strategy in the form of teams across functions. Experiments in new practices are encouraged. A matrix type structure is frequently adopted in this phase.

A matrix structure is a rectangular grid that shows the vertical flow of functional responsibility and a horizontal flow of product or customer responsibility. The provider effectively has two (or more) line organizations with dual lines of authority and a balance of power; two (or more) bosses, each actively participating in strategy setting and governance.

An organization with a matrix structure adopts whatever functions the organization requires to achieve its goals. Functional personnel report to the heads of their respective functions but do not work under their direct supervision. Rather, the work of the functional staff is primarily determined by the leadership of the respective cross-functional product or customer team. The matrix relies on minimal formal vertical control and maximum horizontal control from the use of integrated teams.

The key advantages of a matrix structure:

- Reduces and overcomes functional barriers Increases responsiveness to changing product or customer needs

- Opens up communication between functional specialists

- Provides opportunities for team members from different functions to learn from each other

- Uses the skills of specialized employees who move from product to product, or customer to customer, as needed.

In practice, there can be many problems with a matrix structure. The disadvantages:

- Lacks a control structure that allows staff to develop stable expectations of each other

- Staff can be put off by the ambiguity and role conflict produced

- Potential conflict between functions and product or customer teams over time.

|

| | Figure 6.8 Services through collaboration |

|

6.1.6 Deciding on a Structure

Notice how each phase influences the other over time. The sequences are not always inevitable or linear. Each phase is neither right nor wrong. They are signposts to guide the organization. By understanding the current state, senior executives are better able to decide in what direction, and how far, to move along the centralized-decentralized spectrum.

The key to applying service management organizational development is understanding the following:

- Where the organization is in the sequence

- The range of appropriate options

- Each solution will bring new challenges.

6.1.7 Organizational Change

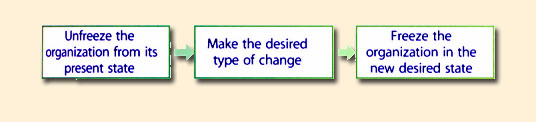

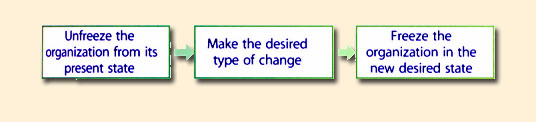

No matter what type of change the organization decides on, there remains the problem of getting the organization to change. Implementing change can be thought of as a three-step process, as in Figure 6.9.

Resistance to change will force the organization to revert to previous behaviours unless steps are taken to refreeze the new changes. Role and task changes are not enough. Managers must actively manage the process.

|

| Figure 6.9 Three-step change process |

- The first step to change is diagnosis. Namely, acknowledge the need for change and the factors prompting it. For example, complaints about service quality have increased or operating costs have escalated. Or morale is low while turnover is high. There is little point in focusing on improving costs if the customer is concerned about quality.

- The second step is determining the desired state. While this can be a difficult planning process with alternative courses of action, it begins with the organization's strategy and desired structure. Is the strategy based on reducing costs or improving quality? Should the organization adopt a product or geographic structure?

- The third step is implementation. This three-step process begins with identifying possible impediments to change. What obstacles are anticipated? For example, functional managers may resist reductions in power or prestige. The more severe the change then the greater the difficulties encountered. Next, decide who will be responsible for implementing changes and controlling the change process. These change agents can be external, as in consultants, or internal, as in knowledgeable managers. External change agents tend to be more objective and less likely to be perceived to be influenced by internal politics, while internal agents tend to have greater local knowledge. Last, decide on which change strategy will most effectively unfreeze, change and refreeze the organization. These techniques fall into two categories: top-down and bottom-up. Top-down is a dramatic restructuring by senior managers while bottom-up is a gradual change by low-level employees. Example techniques include:

- Education and communication

- Participation and empowerment

- Facilitation

- Bargaining and negotiation

- Process consultation

- Team building and inter-group training.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

6.2 Organizational Departmentalization

It is common to think of organizational hierarchies in terms of functions. As the functional groups become larger, think of them in terms of departmentalization. A department can loosely be defined as an organizational activity involving over 20 people. When a functional group grows to departmental size, the organization can reorient the group to one of the following areas or a hybrid thereof:

- Function - preferred for specialization, the pooling of resources and reducing duplication Product - preferred for servicing businesses with strategies of diverse and new products, usually manufacturing businesses

- Market space or customer - preferred for organizing around market structures. Provides differentiation in the form of increased knowledge of and response to customer preferences

- Geography - the use of geography depends on the industry. By providing services in close geographical proximity, travel and distribution costs are minimized while local knowledge is leveraged

- Process - preferred for an end-to-end coverage of a process. Certain basic structures are preferred for certain service strategies, as shown in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Basic organizational structures

Basic Structure Strategic Considerations

Functional specialization

Common standards

Small size

Product Product focus

Strong product knowledge

Market space or customer Service unique to segment

Customer service

Buyer strength

Rapid customer service

Geography On-site services

Proximity to customer for delivery and support

Organization perceived as local

Process Need to minimize process cycle times

Process excellence

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

6.3 Organizational Design

|

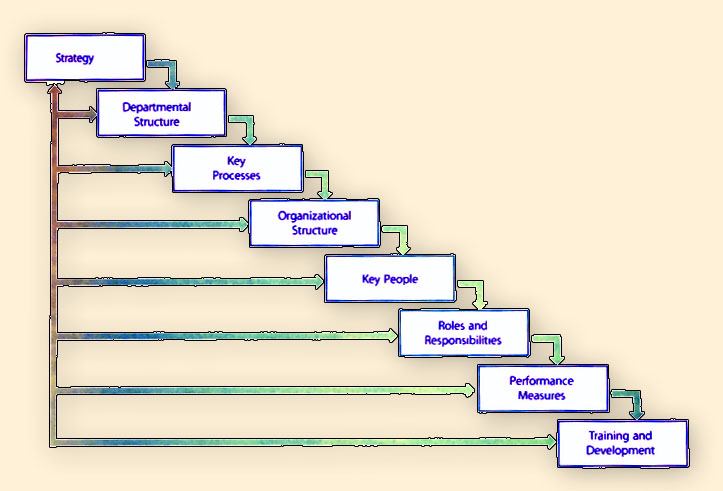

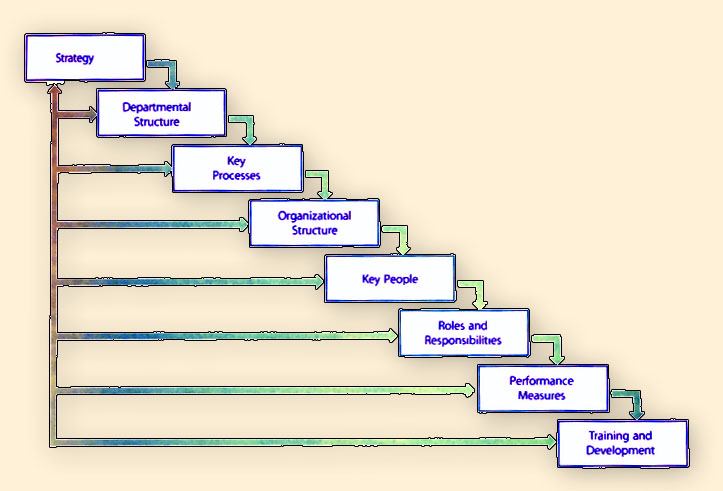

The starting point for organizational design is strategy (Figure 6.10). It sets the direction and guides the criteria for each step of the design process.

It is recommended to decide on a departmentalization structure prior to designing key processes. For example, if the provider's organization will be structured by geography or aligned by customers, the process design will be guided by this criterion. Once key processes are

understood, it is appropriate to begin organizational design (Figure 6.11).

The flow depends on clearly articulated strategic criteria. Processes can be thought of as organizational software - configurable to the requirements of a service strategy. Organizational designers should see each step as an iterative cycle: create basic processes and structures, learn about current and new conditions, and adjust as learning evolves.

|

| | Figure 6.10 Matching Strategic Forces with Organizational Development |

|

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

6.4 Organizational Culture

|

| Figure 6.11 Organization Design Steps |

Organizational culture is the set of shared values and norms that control the IT organization's interactions with each other and customers. Just as an organizational structure can improve performance, so, too, can an organization's culture increase organizational effectiveness.

There are two types of organizational values: terminal and instrumental.

- Terminal values are desired outcomes or end states. IT organizations can adopt any of the following as terminal values: quality, excellence, reliability, innovativeness or profitability. Terminal values are often reflected in the organization's strategic perspective.

- Instrumental values are desired modes of behaviour. IT organizations can adopt any of the following as instrumental values: high standards, respecting tradition and authority, acting cautiously and conservatively, or being frugal.

Terminal and instrumental values are key shapers of behaviour and can therefore produce very different acquisitions fail because of these differences. Culture is transmitted to staff through socialization, training programmes, stories, ceremonies and language.

A service management organizational culture can be analysed through the following steps:

- Identify the terminal and instrumental values of the organization.

- Determine whether the goals, norms and rules of the organization are properly transmitting the value of the organizational culture to staff members. Are there areas for improvement?

- Assess the methods the IT organization uses to introduce new staff. Do these practices help newcomers learn the organization's culture?R

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

6.5 Sourcing Strategy

| 'The next layers of value creation - whether in technology, marketing, biomedicine or manufacturing - are becoming so complex that no single firm or department is going to be able to master them alone.'

Thomas L. Friedman, The World is Flat

|

Outsourcing is the moving of a value-creating activity that was performed inside the organization to outside the organization where it is performed by another company. What prompts an organization to outsource an activity is the same logic that determines whether an organization makes or buys inputs. Namely, does the extra value generated from performing an activity inside the organization outweigh the costs of managing it? This decision can change over time.

A service strategy should enhance an organization's special strengths and core competencies. Each component should reinforce the other. Change any one and you have a different model. As organizations seek to improve their performance, they should consider which competencies are essential and know when to extend their capabilities by partnering in areas both inside and outside their enterprise. Service sourcing is another example of the Separation of Concerns (SoC) principle. This time it is a separation of the 'what' from the 'who'.

Case example 13: Service Strategy

During the early 2000s, companies rushed to implement a service strategy based on labour arbitrage: service providers decrease labour costs by making use of less expensive off-shore resources. The strategic intent is to make a provider's value proposition more compelling through lower cost structures.

While costs did indeed decrease for customers, providers were unable to make long-term gains to their financial bottom line.

Why?

|

IT and business services are increasingly delivered by service providers outside the enterprise, and by the internal organization. Making an informed service sourcing decision requires finding a balance between thorough qualitative and quantitative considerations. Historically, the financial business case is the primary basis for most sourcing decisions. These analyses include pure cost savings, lower capital investments, investment redirections and long-term cost containment. Unfortunately, most

financial analyses do not include all the costs related to sourcing, leading to difficult sourcing relationships with unexpected costs and service issues. If costs are a primary driver for a sourcing decision, include financials for service transition, relationship management, legal support, incentives, training, tools licensing implications and process rationalization, among others.

6.5.1 Deciding What to Source

A business's strategy formulation is the search for competitive differentiation through the redeployment of resources and capabilities. When a business decides to source services it is in essence deciding to source resources and capabilities. If candidates are only peripherally related to the business's strategic themes and are available in competitive markets then they should be considered. Once candidates for sourcing are identified, the following questions are intended to clarify matters:

- Do the candidate services improve the business' resources and capabilities?

- How closely are the candidate services connected to the business's competitive and strategic resources and capabilities?

- Do the candidate services require extensive interactions between the service providers and the business's competitive and strategic resources and capabilities?

If the responses uncover minimal dependencies and infrequent interactions between the sourced services and the business's competitive and strategic positioning, then the candidates are strong contenders.

If candidates for sourcing are closely related to the business's competitive or strategic positioning, then care must be taken. Such sourcing structures are particularly vulnerable to:

- Substitution - 'Why do I need the service provider when its supplier can offer the same services?' The sourced vendor develops competing capabilities and replaces the sourcing organization.

- Disruption - The sourced vendor has a direct impact on quality or reputation of the sourcing organization.

- Distinctiveness - The sourced vendor is the source of distinctiveness for the sourcing organization.

The sourcing organization then becomes particularly dependent on the continued development and success of the second organization.

Do not confuse distinctive activities with critical activities. Critical activities do not necessarily refer to activities that may be distinctive to the service provider. Take, for example, customer service. Customers may believe it is critical, but if it does not differentiate the provider from competing alternatives then it is not distinctive, it is context.

This does not mean critical activities are not important. Contextual activities are not of secondary importance. It means they do not provide the differentiating benefit that generates value. One service provider's context may be

another's distinctiveness. What is distinctive today may over time become context. Contextual processes may be recombined into distinctive processes. Here is a basic test:

- Does the customer or market space expect the service provider to do this activity? (context)

- Does the customer or market space give the service provider credit for performing this activity exceptionally well? (distinctiveness )

Early adopters of airline kiosks, for example, differentiated themselves through self-service technology (Mode-E). While kiosks were a distinctive activity central to the service strategy, it was hardly critical. Years later, customers expect kiosks at all locations for every airline. Every major airline considers it a critical activity but not distinctive - it no longer differentiates. Hence airlines consolidate or source this critical activity. They collaborate with partner airlines to provide kiosks any member airline may use. They source kiosks from Type III providers who place them in corporate locations, hotels and public places.

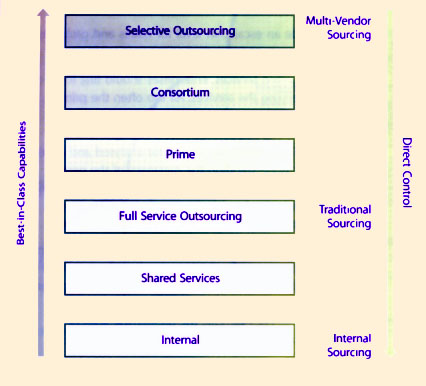

6.5.2 Sourcing Structures

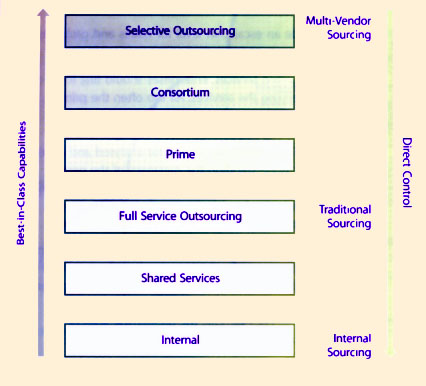

|

| Figure 6.12 Service sourcing structures |

| Sourcing Structure | Description

|

| Internal (Type I) | The provision and delivery of services by internal staff. Does not typically include

standardization of service delivery across business units.

Provides the most control but also the most limited in terms of scale.

|

| Shared Services (Type II) | An internal business unit. Typically operates its profit and loss, and a chargeback mechanism. If

cost recovery is not used, then it is Internal not Shared Services.

Lower costs than Internal with a similar degree of control. Improved standardization but

limited in terms of scale.

|

| Full Service Outsourcing | A single contract with a single service provider. Typically involves significant asset transfer.

Provides improved scale but limited in terms of best-in-class capabilities. Delivery risks are higher

than Prime, Consortium or Selective Outsourcing as switching to an alternative is difficult.

|

| Prime | A single contract with a single service provider who manages service delivery but engages

multiple providers to do so. The contract stipulates that the prime vendor will leverage the

capabilities of other best-in-class service providers.

Capabilities and risk are improved from Single-Vendor Outsourcing but complexity is increased.

|

| Consortium | A collection of service providers explicitly selected by the service recipient. All providers are

required to come together and present a unified management interface.

Fulfils a need that cannot be satisfied by any Single-Vendor Outsourcer. Provides best-in-class

capabilities with greater control than Prime. Risk is introduced in the form of providers forced

to collaborate with competitors.

|

| Selective Outsourcing | A collection of service providers explicitly selected and managed by the service recipient.

This is the most difficult structure to manage. The service recipient is the service integrator,

responsible for gaps or cross-provider disputes.

The term Co-Sourcing refers to a special case of Selective Outsourcing. In this variant, the

service recipient maintains an Internal or Shared Services structure and combines it with

external providers. The service recipient is the service integrator.

|

| Table 6.2 Service sourcing structures |

The dynamics of service sourcing require businesses to formally address provisions for a sourcing strategy, the structure and role of the retained organization, and the impacted decision rights processes. When sourcing services, the enterprise retains the responsibility for the adequacy of services delivered. Therefore, the enterprise retains key overall responsibility for governance. The enterprise should adopt a formal governance approach in order to create a working model for managing its outsourced services as well as the assurance of value delivery. This includes planning for the organizational change precipitated by the sourcing strategy and a formal and verifiable description as to how decisions on services are made. Figure 6.12 and Table 6.2 describes the generic forms of service sourcing structures.

The selection of a sourcing structure should be balanced with acceptable risks and levels of control. The method an organization uses to manage a sourcing relationship depends greatly on the sourcing organization's characteristics such as degrees of centralization, standards and process maturity. In general, the sourcing organization should excel in establishing a set of relationship standards and processes. Other key responsibilities are to:

- Monitor the performance of the agreements and the overall relationship with providers.

- Manage the sourcing agreements.

- Provide an escalation level for issues and problems.

- Ensure prioritization for providers.

When sourcing services, enterprises should first focus on clearly defining the services. All too often the primary focus is on the reporting structures and the resources aligned to those structures. Resource alignment and organizational structures should be analyzed and adjusted only after understanding the dynamics of the new or enhanced services. This affords the opportunity to remove redundancies and ambiguities, and chokepoints and dysfunctions prior to creating workflows.

Once the resource and organizational discussion begins, be sure to account for the introduction of new critical skills. While highly dynamic, these competencies generally fall into three categories: business, technical and behavioural. For example, the greater the level of outsourcing, the greater the need for business and behavioural skills. The greater the level of internal sourcing, the greater the need for technical skills.

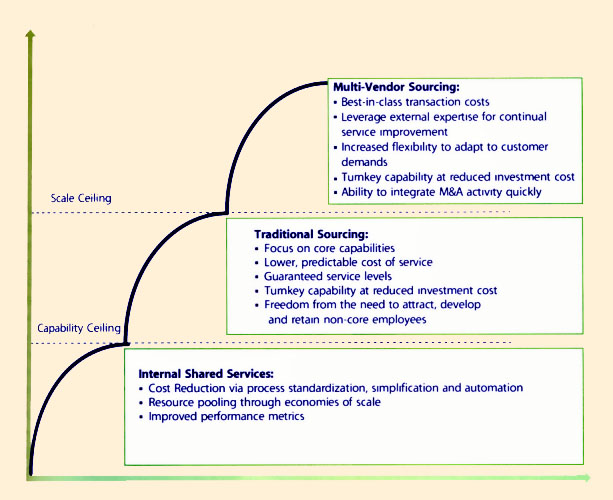

6.5.3 Multi-Vendor Sourcing

The approach of sourcing services through multiple providers has emerged as a good practice. The enterprise maintains a strong relationship with each provider, spreading the risk and reducing costs. The challenges are in governance and managing the multiple providers. When sourcing multiple providers, the following issues should be carefully evaluated:

- Technical complexity: sourcing is useful for standardized service processes. Be mindful that as customization increases it is more difficult to achieve the desired efficiencies.

- Organizational interdependencies: contractual vehicles should be carefully structured to the dynamics of multiple organizations. Incentives, training, and other intangibles can have significant long-term effects.

- Integration planning: carefully consider the need for integration planning and solutions. This can take the form of standardized reporting and service reporting, or installed technology and protocols that integrate tools and data.

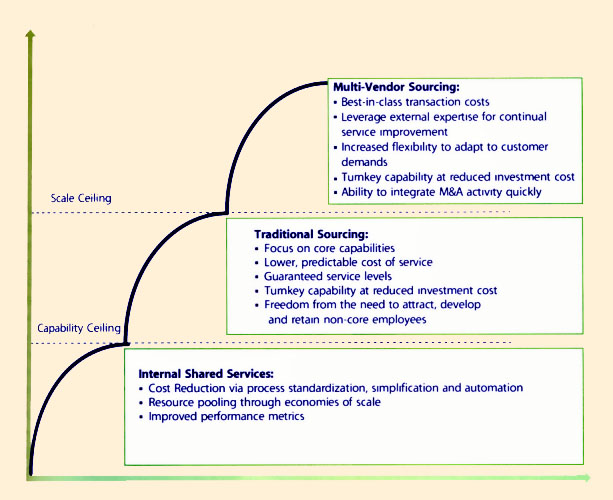

There are multiple approaches and varying degrees in sourcing. How far up an organization is willing to go with sourcing depends on the business objectives to be achieved and constraints to overcome (Figure 6.13). Regardless of the sourcing approach, senior executives must carefully evaluate provider attributes. The following is a useful checklist:

- Demonstrated competencies: in terms of staff, use of technologies, innovation, industry experience and certifications (ISO/IEC 20000)

- Track record: in terms of service quality attained, financial value created and demonstrated commitment to continual improvement

- Relationship dynamics: in terms of vision and strategy, the cultural fit, relative size of contract in their portfolio and quality of relationship management

- Quality of solutions: relevance of services to your requirements, risk management and performance benchmarks

- Overall capabilities: in terms of financial strength, resources, management systems, and scope and range of services.

|

| Figure 6.13 The service sourcing staircase |

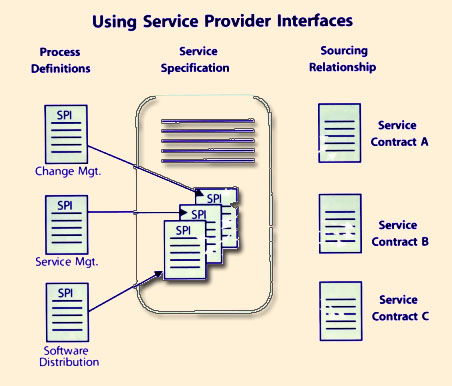

6.5.4 Service Provider Interfaces

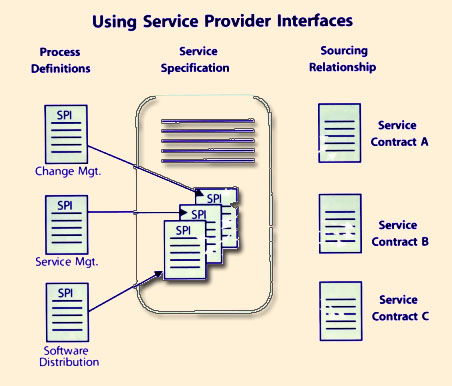

To support development of sourcing relationships in a multi-vendor environment, guidelines and reference points (technical, procedural, organizational) are needed between the various service providers. These reference points can be provided through the use of Service Provider Interfaces (SPI) (Figure 6.14).

SPIs help coordinate end-to-end management of critical services. The Service Catalogue drives the service specifications, which are part of, or extensions to, standard process definitions. Responsibilities and service levels are negotiated at the time of service relationship contracting, and include:

- Identification of integration points between various management processes of the client and service provider

- Identification of specific roles and responsibilities for managing the ongoing systems management relationship with both parties

- Identification of relevant systems management information that needs to be communicated to the customer on an ongoing basis.

Process SPI definitions consist of:

- Technology prerequisites (e.g. management tool standards or prescribed protocols)

- Data requirements (e.g. specific events or records), formats (i.e. data layouts), interfaces (e.g. APIs, firewall ports) and protocols (e.g. SNMP, XML)

- Non-negotiable requirements (e.g. practices, activities, operating procedures)

- Required roles/responsibilities within the service provider and customer organizations

- Response times and escalations.

SPIs are defined, maintained and owned by process owners. Others involved in the definition include:

- Business representatives, who negotiate the SPI requirements and are responsible for managing the strategic relationships with and between service providers

- Service provider process coordinator(s) who take operational responsibility for ensuring the operational processes are synchronized.

6.5.5 Sourcing Governance

|

| | Figure 6.14 Service provider interfaces |

|

There is a frequent misunderstanding of the definition of governance, particularly in a sourcing context. Companies have used the word interchangeably with 'vendor management,' 'retained staff,' and 'sourcing management organization'. Governance is none of these.

Management and governance are different disciplines. Management deals with making decisions and executing processes. Governance only deals with making sound decisions. It is the framework of decision rights that encourage desired behaviours in the sourcing and the sourced organization. When companies confuse management and governance, they inevitably focus on execution at the expense of strategic decision making. Both are vitally important. Further complicating matters is the requirement of sharing decision rights with the service providers. When a company places itself in a position to make operational decisions on behalf of an outsourcer, the outcomes are inevitably poor service levels and contentious relationship management.

Governance is invariably the weakest link in a service sourcing strategy. A few simple constructs have been shown to be effective at improving that weakness:

- A governance body. By forming a manageably sized governance body with a clear understanding of the Service Sourcing strategy, decisions can be made without escalating to the highest levels of senior management. By including representation from each service provider, stronger decisions can be made.

- Governance domains. Domains can cover decision making for a specific area of the Service Sourcing strategy. Domains can cover, for example, Service Delivery, Communication, Sourcing Strategy or Contract Management. Remember, a governance domain does not include the responsibility for its execution, only its strategic decision making.

- Creation of a decision-rights matrix. This ties all three recommendations together. RACI or RASIC charts are common forms of a decision-rights matrix.

|

Partnering with providers who are ISO/IEC 20000

compliant is an important element is reducing the risk of Service Sourcing. Organizations who have achieved this certification are more likely to meet service levels on a sustained basis. This credential is particularly important in multi-sourced environments where a common framework promotes better integration. Multi-sourced environments require common language, integrated processes and a management structure between internal and external providers. ISO/IEC 20000 does not provide all of this but it provides a foundation on which it can be built.

Published in 2005, ISO/IEC 20000 is the first formal international standard specific to IT Service Management. An organization comfortable with ITIL will find no difficulty in interpreting ISO/IEC 20000.

Service providers should also consider the eSourcing Capability Model for Service Providers Version 2.0 (eSCMSP v2) developed by a consortium of service providers led by Carnegie Mellon University. Guidance in this model is specific to sourcing of IT-enabled services. The eSCM-SP provides a framework for organizations to develop their service management capabilities from a sourcing perspective. Organizations can have their sourcing capabilities certified by Carnegie Mellon to be one of four capability levels, based on the publicly available eSCM-SP Reference Model and related Capability Determination Methods. The requirements of eSCM-SP v2 are complementary to ISO/IEC 20000.

6.5.6 Critical Success Factors

The factors for a Service Sourcing strategy frequently depend on:

- Desired outcomes, such as cost reduction, improved service quality or diminished business risk

- The optimal model for delivering the service

- The best location to deliver the service, such as local, off-shore or on-shore.

The recommended approach to deciding on a strategy includes:

- Analyse the organization's internal service management competencies

- Compare those findings with industry benchmarks

- Assess the organization's ability to deliver strategic value.

The approach will likely lead to these scenarios:

- If the organization's internal service management competence is high and also provides strategic value, then an internal or shared services strategy is the most likely option. The organization should continue to invest internally, leveraging high-value expert providers to refine and enhance the service management competencies.

- If the organization's internal service management competence is low but provides strategic value, then outsourcing is an option provided services can be maintained or improved through the use of high-value providers.

- If the organization's internal service management competence is high but does not provide strategic value, then there are multiple options. The business may want to invest in its service capabilities so that they do provide strategic value or it may sell off this service capability, because it may be of greater value to a third party.

- If the organization's internal service management competence and strategic value are low, then they should be considered candidates for outsourcing.

|

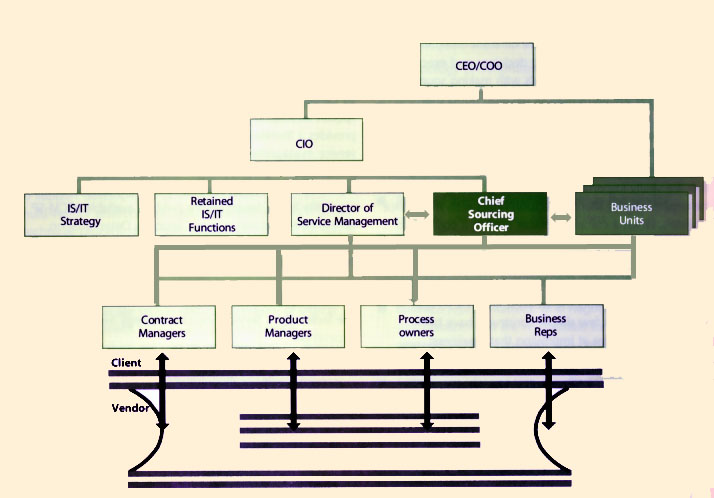

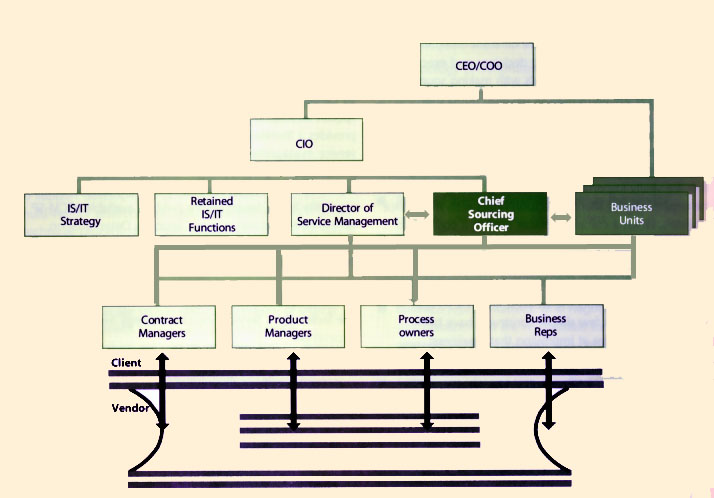

| Figure 6.15 Chief Sourcing Officer |

Prior to any implementation, an organization should establish and maintain a baseline of its performance metrics. Without such metrics, it will be difficult to assess the true impact and trends of a service sourcing implementation. Measurements can take on two forms:

- Business metrics: financial savings, service level improvements, business process efficiency

- Customer metrics: availability and consistency of services, increased offerings, quality of service.

6.5.7 Sourcing Roles and Responsibilities

A key role to champion the sourcing strategy and lead and direct the sourcing office capabilities is the Chief Sourcing Officer (Figure 6.15).

The Chief Sourcing officer

- Champions the sourcing strategy and the sourcing office

- Works closely with the CIO to develop a sourcing strategy that will determine which roles and responsibilities are best assumed by internal personnel and in which areas external resources should be deployed; sets guiding principles for governance

- Coordinates and rallies a mix of external and internal people towards goals through an empowerment-and-trust style, rather than the command-and-control hierarchical structure used with internal resources

- Is an integrator, coordinator, communicator, leader, coach: creates a shared identity among external and internal sources so that team members identify themselves first and foremost with the initiative at hand

- Has the ability to interact at the executive level, and to inspire and lead at the delivery level.

Other key roles should be clearly defined for coordinating activities across multiple service providers, as shown in Table 6.3.

| Role | Description | Key competencies

|

| Director of service management | Senior executive who understands the business and defines, plans, purchases and manages all aspects of service delivery on behalf of business units |

Authority and seniority to prioritize and define services for business units

Large-scale service and operations management Financial and commercial management

Governance, negotiation and Contract Management

|

| Contract manager | Constructs, negotiates, monitors and manages the legal and commercial contract on behalf of the sourcing_ organization | Contract Management for large scale service provision

Negotiation and conflict resolution

Service definition and management

Translation of business into contractual requirements

|

| Product manager | Defines, plans, purchases and manages sourced elements of the service and performance on behalf of sourcing organization | Authority and seniority to prioritise and define sourcing needs for specific elements of the service

|

| Process Owner | Interface with business users and functions to review, define and authorize current and future process models. Aim to identify and standardize best practices | Capability and process definition Process mapping Service monitoring

Managing user forums e.g. Joint Application Development, Conference Room Pilot

Best practice identification, capture and rollout

|

| Business representatives

| Primary service recipient on behalf of each business unit who define business requirements, monitor service, raise service requests and own budgets | Knowledge of specific business functions

Requirements gathering, definition and prioritisation

Service monitoring Managing user forums

|

| Table 6.3 Sourcing roles and responsibilities |

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)