Service Operations

5. Common Service Operation Activities

Chapter 4 dealt with the processes required for effective Service Operation and Chapter 6 will deal with the organizational aspects. This chapter focuses on a number of operational activities that ensure that technology is aligned with the overall Service and Process objectives. These activities are sometimes described as processes, but in reality they are sets of specialized technical activities all aimed at ensuring that the technology required to deliver and support services is operating effectively and efficiently.

These activities will usually be technical in nature - although the exact technology will vary depending on the type of services being delivered. This publication will focus on the activities required to manage IT.

Important note on managing technology

It is tempting to divorce the concept of Service Management from the management of the infrastructure that is used to deliver those services.

In reality, it is impossible to achieve quality services without aligning and 'gearing' every level of technology (and the people who manage it) to the services being provided. Service Management involves people, process and technology.

In other words, the common Service Operation activities are not about managing the technology for the sake of having good technology performance. They are about achieving performance that will integrate the technology component with the people and process components to achieve service and business objectives. See Figure 5.1 for examples of how technology is managed in maturing organizations.

|

|

| Figure 5.1 Achieving maturity in Technology Management |

Figure 5.1 illustrates the steps involved in maturing from a technology-centric organization to an organization that harnesses technology as part of its business strategy. Figure 5.1 further outlines the role of Technology Managers in organizations of differing maturity. The diagram is not comprehensive, but it does provide examples of the way in which technology is managed in each type of organization. The bold headings indicate the major role played by IT in managing technology. The text in the rows describes the characteristics of an IT department at each level.

The purpose of this diagram in this chapter is as follows:

- This chapter focuses on Technical Management activities, but there is no single way of representing them. A less mature organization will tend to see these activities as ends in themselves, not a means to an end. A more mature organization will tend to subordinate these activities to higher-level Service Management objectives. For example, the Server Management team will move from an insulated department, focused purely on managing servers, to a team that works closely with other Technology Managers to find ways of increasing their value to the business.

- To make and reinforce the point that there is no 'right' way of grouping and organizing the departments that perform these services. Some readers might interpret the headings in this chapter as the names of departments, but this is not the case. The aim of this chapter is to identify the typical technical activities involved in Service Operation. Organizational aspects are discussed in Chapter 6.

- The Service Operation activities described in the rest of this chapter are not typical of any one of the levels of maturity. Rather, the activities are usually all present in some form at all levels. They are just organized and managed differently at each level.

In some cases a dedicated group may handle all of a process or activity while in other cases processes or activities may be shared or split between groups. However, by way of broad guidance, the following sections list the required activities under the functional groups most likely to be involved in their operation. This does not mean that all organizations have to use these divisions. Smaller organizations will tend to assign groups of these activities (if they are needed at all) to single departments, or even individuals.

Finally, the purpose of this chapter is not to provide a detailed analysis of all the activities. They are specialized, and detailed guidance is available from the platform vendors and other, more technical, frameworks; new categories will be added continually as technology evolves. This chapter simply aims to highlight the importance and nature of technology management for Service Management in the IT context.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.1 Monitoring And Control

The measurement and control of services is based on a continual cycle of monitoring, reporting and subsequent action. This cycle is discussed in detail in this section because it is fundamental to the delivery, support and improvement of services.

It is also important to note that, although this cycle takes place during Service Operation, it provides a basis for setting strategy, designing and testing services and achieving meaningful improvement. It is also the basis for SLM measurement. Therefore, although monitoring is performed by Service Operation functions, it should not be seen as a purely operational matter. All phases of the Service Lifecycle should ensure that measures and controls are clearly defined, executed and acted upon.

5.1.1 Definitions

| Monitoring refers to the activity of observing a situation to detect changes that happen over time.

|

In the context of Service Operation, this implies the following:

- Using tools to monitor the status of key CIs and key operational activities

- Ensuring that specified conditions are met (or not met) and, if not, to raise an alert to the appropriate group (e.g. the availability of key network devices)

- Ensuring that the performance or utilization of a component or system is within a specified range (e.g. disk space or memory utilization)

- To detect abnormal types or levels of activity in the infrastructure (e.g. potential security threats)

- To detect unauthorized changes (e.g. introduction of software)

- To ensure compliance with the organization's policies (e.g. inappropriate use of e-mail)

- To track outputs to the business and ensure that they meet quality and performance requirements

- To track any information that is used to measure Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

| Reporting refers to the analysis, production and distribution of the output of the monitoring activity.

|

In the context of Service Operation, this implies the following:

- Using tools to collate the output of monitoring information that can be disseminated to various groups, functions or processes

- Interpreting the meaning of that information

- Determining where that information would best be used

- Ensuring that decision makers have access to the information that will enable them to make decisions

- Routing the reported information to the appropriate person, group or tool.

Control refers to the process of managing the utilization or behaviour of a device, system or service. It is important to note, though, that simply manipulating a device is not the same as controlling it. Control requires three conditions:

- The action must ensure that behaviour conforms to a defined standard or norm

- The conditions prompting the action must be defined, understood and confirmed

- The action must be defined, approved and appropriate for these conditions.

|

In the context of Service Operation, control implies the following:

- Using tools to define what conditions represent normal operations or abnormal operations

- Regulate performance of devices, systems or services

- Measure availability

- Initiate corrective action, which could be automated (e.g. reboot a device remotely or run a script), or manual (e.g. notify operations staff of the status).

5.1.2 Monitor Control Loops

|

| Figure 5.2 The Monitor Control Loop |

The most common model for defining control is the Monitor Control Loop. Although it is a simple model, it has many complex applications within IT Service Management. This section will define the basic concepts of the Monitor Control Loop Model and subsequent sections will show how important these concepts are for the Service Management Lifecycle.

Figure 5.2 outlines the basic principles of control. A single activity and its output are measured using a predefined norm, or standard, to determine whether it is within an acceptable range of performance or quality. If not, action is taken to rectify the situation or to restore normal performance.

Typically there are two types of Monitor Control Loops:

- Open Loop Systems are designed to perform a specific activity regardless of environmental conditions. For example, a backup can be initiated at a given time and frequency - and will run regardless of other conditions.

- Closed Loop Systems monitor an environment and respond to changes in that environment. For example, in network load balancing a monitor will evaluate the traffic on a circuit. If network traffic exceeds a certain range, the control system will begin to route traffic across a backup circuit. The monitor will continue to provide feedback to the control system, which will continue to regulate the flow of network traffic between the two circuits.

To help clarify the difference, solving Capacity Management through over-provisioning is open loop; a load-balancer that detects congestion/failure and redirects capacity is closed loop.

5.1.2.1 Complex Monitor Control Loop

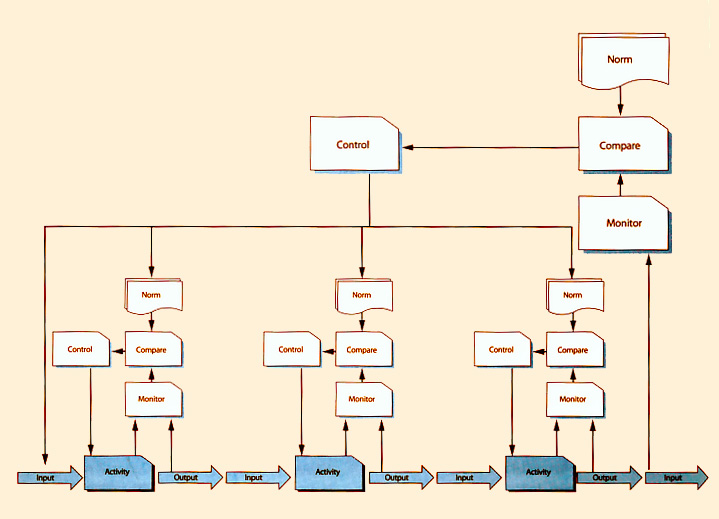

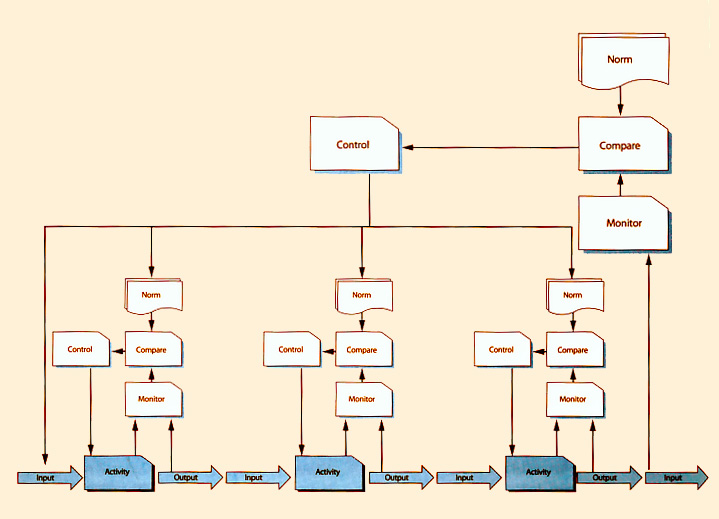

The Monitor Control Loop in Figure 5.2 is a good basis for defining how Operations Management works, but within the context of ITSM the situation is far more complex. Figure 5.3 illustrates a process consisting of three major activities. Each one has an input and an output, and the output becomes an input for the next activity.

In this diagram, each activity is controlled by its own Monitor Control Loop, using a set of norms for that specific activity. The process as a whole also has its own Monitor Control Loop, which spans all the activities and ensures that all norms are appropriate and are being followed.

|

| Figure 5.3 Complex Monitor Control Loop |

In Figure 5.3 there is a double feedback loop. One loop focuses purely on executing a defined standard, and the second evaluates the performance of the process and also the standards whereby the process is executed. An example of this would be if the first set of feedback loops at the bottom of the diagram represented individual stations on an assembly line and the higher-level loop represented Quality Assurance.

The Complex Monitor Control Loop is a good organizational learning toolR .

The first level of feedback at individual activity level is concerned with monitoring and responding to data (single facts, codes or pieces of information). The second level is concerned with monitoring and responding to information (a collection of a number of facts about which a conclusion may be drawn). Refer to the Service Transition publication for a full discussion on Data, Information, Knowledge and Wisdom.

All of this is interesting theory, but does not explain how the Monitor Control Loop concept can be used to operate IT services. And especially - who defines the norm? Based on what has been described so far, Monitor Control Loops can be used to manage:

- The performance of activities in a process or procedure. Each activity and its related output can potentially be measured to ensure that problems with the process are identified before the process as a whole is completed. For example, in Incident Management, the Service Desk monitors whether a technical team has accepted an incident in a specified time. If not, the incident is escalated. This is done well before the target resolution time for that incident because the aim of escalating that one activity is to ensure that the process as whole is completed in time.

- The effectiveness of a process or procedure as a whole. In this case the 'activity' box represents the entire process as a single entity. For example, Change Management will measure the success of the process by checking whether a change was implemented on time, to specification and within budget.

- The performance of a device. For example, the 'activity' box could represent the response time of a server under a given workload.

- The performance of a series of devices. For example, the end user response time of an application across the network.

To define how to use the concept of Monitor Control Loops in Service Management, the following questions need to be answered:

- How do we define what needs to be monitored?

- What are the appropriate thresholds for each of these?

- How will monitoring be performed (manual or automated)?

- What represents normal operation?

- What are the dependencies for normal operation?

- What happens before we get the input?

- How frequently should the measurement take place?

- Do we need to perform active measurement to check whether the item is within the norm or do we wait until an exception is reported (passive measurement)?

- Is Operations Management the only function that performs monitoring?

- If not, how are the other instances of monitoring related to Operations Management?

- If there are multiple loops, which processes are responsible for each loop?

The following sections will expand on the concept of Monitor Control Loops and demonstrate how these questions are answered.

5.1.2.2 The ITSM Monitor Control Loop

In ITSM, the complex Monitor Control Loop can be represented as shown in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 can be used to illustrate the control of a process or of the components used to deliver a service. In this diagram the word 'activity' implies that it refers to a process. To apply it to a service, an 'activity' could also be a 'Cl'. There are a number of significant features in Figure 5.4.

|

| Figure 5.4 ITSM Monitor Control Loop |

- Each activity in a Service Management process (or each component used to provide a service) is monitored as part of the Service Operation processes. The operational team or department responsible for each activity or component will apply the Monitor Control Loop as defined in the process, and using the norms that were defined during the Service Design processes. The role of Operational Monitoring and Control is to ensure that the process or service functions exactly as specified, which is why they are primarily concerned with maintaining the status quo.

- The norms and Monitoring and Control mechanisms are defined in Service Design, but they are based on the standards and architectures defined during Service Strategy. Any changes to the organization's Service Strategy, architecture, service portfolios or Service Level Requirements will precipitate changes to what is monitored and how it is controlled.

- The Monitor Control Loops are placed within the context of the organization. This implies that Service Strategy will primarily be executed by Business and IT Executives with support from vendor account managers. Service Design acts as the bridge between Service Strategy and Service Operation and will typically involve representatives from all groups. The activities and controls will generally be executed by IT staff (sometimes involving users) and supported by IT Managers and the vendors. Service Improvement spans all areas, but primarily represents the interests of the business and its users.

- Notice that the second level of monitoring in this complex Monitor Control Loop is performed by the

CSI processes through Service Strategy and Service

Design. These relationships are represented by the

numbered arrows in Figure 5.4 as follows:

- Arrow 1. In this case CSI has recognized that the service will be improved by making a change to the Service Strategy. This could be the result of the business needing a change to the Service Portfolio, or that the architecture does not deliver what was expected.

- Arrow 2. In this case the Service Level Requirements need to be adjusted. It could be that the service is too expensive; or that the configuration of the infrastructure needs to be changed to enhance performance; or because Operations Management is unable to maintain service quality in the current architecture.

- Arrow 3. In this case the norms specified in Service Design are not being adhered to. This could be because they are not appropriate or executable, or because of a lack of education or a lack of communication. The norms and the lack of compliance need to be investigated and action taken to rectify the situation.

Service Transition provides a major set of checks and balances in these processes. It does so as follows:

- For new services, Service Transition will ensure that the technical architectures are appropriate; and that the Operational Performance Standards can be executed. This in turn will ensure that the Service Operation teams or departments are able to meet the Service Level Requirements.

- For existing services, Change Management will manage any of the changes that are required as part of a control (e.g. tuning) as well as any changes represented by the arrows labelled 1, 2 and 3. Although Service Transition does not define strategy and design services per se, it provides coordination and assurance that the services are working, and will continue to work, as planned.

Why is this loop covered under Service Operation?

Figure 5.4 represents Monitoring and Control for the whole of IT Service Management. Some readers of the Service Operation publication may feel that it should be more suitably covered in the Service Strategy publication.

However, Monitoring and Control can only effectively be deployed when the service is operational. This means that the quality of the entire set of IT Service Management processes depends on how they are monitored and controlled in Service Operation.

The implications of this are as follows:

- Service Operation staff are not the only people with an interest in what is monitored and how they are controlled.

- While Service Operation is responsible for monitoring and control of services and components, they are acting as stewards of a very important part of the set of ITSM Monitoring and Control loops.

- If Service Operation staff define and execute Monitoring and Control procedures in isolation, none of the Service Management processes or functions will be fully effective. This is because the Service Operation functions will not support the priorities and information requirements of the other processes, e.g. attempting to negotiate an SLA when the only data available is page-swap rates on a server and detailed bandwidth utilization of a network.

|

5.1.2.3 Defining What Needs To Be Monitored

The definition of what needs to be monitored is based on understanding the desired outcome of a process, device or system. IT should focus on the service and its impact on the business, rather than just the individual components of technology. The first question that needs to be asked is What are we trying to achieve?'.

5.1.2.4 Internal and External Monitoring and Control

At the outset, it will become clear that there are two levels of monitoring:

- Internal Monitoring and Control: Most teams or departments are concerned about being able to execute effectively and efficiently the tasks that have been assigned to them. Therefore, they will monitor the items and activities that are directly under their control. This type of monitoring and control focuses on activities that are self-contained within that team or department. For example, the Service Desk Manager will monitor the volume of calls to determine how many staff need to be available to answer the telephone.

- External Monitoring and Control: Although each team or department is responsible for managing its own area, they do not act independently. Every task that they perform, or device that they manage, has an impact on the success of the organization as a whole. Each team or department will also be controlling items and activities on behalf of other groups, processes or functions. For example, the Server Management team will monitor the CPU performance on key servers and perform workload balancing so that a critical application is able to stay within performance thresholds set by Application Management.

The distinction between Internal and External Monitoring is an important one. If Service Operation focuses only on Internal Monitoring, it will have very well-managed infrastructure, but no way of understanding or influencing the quality of services. If it focuses only on External Monitoring, it will understand how poor the service quality is, but will have no idea what is causing it or how to change it.

In reality, most organizations have a combination of Internal and External Monitoring, but in many cases these are not linked. For example, the Server Management team knows exactly how well the servers are performing and the Service Level Manager knows exactly how the users perceive the quality of service provided by the servers. However, neither of them knows how to link these metrics to define what level of server performance represents good quality service. This becomes even more confusing when server performance that is acceptable in the middle of the month, is not acceptable at month-end.

5.1.2.5 Defining Objectives For Monitoring And Control

Many organizations start by asking the question 'What are we managing?'. This will invariably lead to a strong Internal Monitoring System, with very little linkage to the real outcome or service that is required by the business.

The more appropriate question is 'What is the end result of the activities and equipment that my team manages?'. Therefore the best place to start, when defining what to monitor, is to determine the required outcome.

The definition of Monitoring and Control objectives should ideally start with the definition of the Service Level Requirements documents (see Service Design publication). These will specify how the customers and users will measure the performance of the service, and are used as input into the Service Design processes. During Service Design, various processes will determine how the service will be delivered and managed. For example, Capacity Management will determine the most appropriate and cost-effective way to deliver the levels of performance required. Availability Management will determine how the infrastructure can be configured to provide the fewest points of failure.

If there is any doubt about the validity or completeness of objectives, the COBIT framework provides a comprehensive, high-level set of objectives as a checklist. More information on COBIT is provided in Appendix A of this publication.

The Service Design Process will help to identify the following sets of inputs for defining Operational Monitoring and Control norms and mechanisms:

They will work with customers and users to determine how the output of the service will be measured. This will include measurement mechanisms, frequency and sampling. This part of Service Design will focus specifically on the Functional Requirements.

- They will identify key CIs, how they should be configured and what level of performance and availability is required in order to meet the agreed Service Levels.

- They will work with the developers and vendors of the CIs that make up each service to identify any constraints or limitations in those components.

- All support and delivery teams and departments will need to identify what information will help them to execute their role effectively. Part of the Service Design and development will be to instrument each service so that it can be monitored to provide this information, or so that it can generate meaningful events.

All of this means that a very important part of defining what Service Operation monitors and how it exercises control is to identify the stakeholders of each service.

Stakeholders can be defined as anyone with an interest in the successful delivery and receipt of IT services. Each stakeholder will have a different perspective of what it will take to deliver or receive an IT service. Service Operation will need to understand each of these perspectives in order to determine exactly what needs to be monitored and what to do with the output.

Service Operation will therefore rely on SLM to define exactly who these stakeholders are and how they contribute to or use the service. This is discussed more fully in the Service Design and Continual Service Improvement publications.

Note on Internal and External Monitoring Objectives

The required outcome could be internal or external to the Service Operation functions, although it should always be remembered that an internal action will often have an external result. For example, consolidating servers to make them easier to manage may result in a cost saving, which will affect the SLM negotiation and review cycle as well as the Financial Management processes.

|

5.1.2.6 Types Of Monitoring

There are many different types of monitoring tool and different situations in which each will be used. This section focuses on some of the different types of monitoring that can be performed and when they would be appropriate.

Active versus Passive Monitoring

- Active Monitoring refers to the ongoing 'interrogation' of a device or system to determine its status. This type of monitoring can be resource intensive and is usually reserved to proactively monitor the availability of critical devices or systems; or as a diagnostic step when attempting to resolve an Incident or diagnose a problem.

- Passive Monitoring is more common and refers to generating and transmitting events to a 'listening device' or monitoring agent. Passive Monitoring depends on successful definition of events and instrumentation of the system being monitored (see section 4.1).

Reactive versus Proactive

- Reactive Monitoring is designed to request or trigger action following a certain type of event or failure. For example, server performance degradation may trigger a reboot, or a system failure will generate an incident. Reactive monitoring is not only used for exceptions. It can also be used as part of normal operations procedures, for example a batch job completes successfully, which prompts the scheduling system to submit the next batch job.

- Proactive Monitoring is used to detect patterns of events which indicate that a system or service may be about to fail. Proactive monitoring is generally used in more mature environments where these patterns have been detected previously, often several times. Proactive Monitoring tools are therefore a means of automating the experience of seasoned IT staff and are often created through the Proactive Problem Management process (see Continual Service Improvement publication).

Please note that Reactive and Proactive Monitoring could be active or passive, as per Table 5.1.

| | Active | Passive

|

| Reactive

| Used to diagnose which device is causing the failure and under what conditions (e.g. 'ping' a device, or run and track a sample transaction through a series of devices)

Requires knowledge of the infrastructure topography and the mapping of services to CIs

| Detects and correlates event records to determine the meaning of the events and the appropriate action (e.g. a user logs in three times with the incorrect password, which generates represents a security exception and is escalated through Information Security Management procedures)

Requires detailed knowledge of the normal operation of the infrastructure and services

|

| Proactive

| Used to determine the real-time status of a device, system or service - usually for critical components or following the recovery of a failed device to ensure that it is fully recovered (i.e. is not going to cause further incidents)

| Event records are correlated over time to build trends for Proactive Problem Management.

Patterns of events are defined and programmed into correlation tools for future recognition.

|

| Table 5.1 Active and Passive Reactive and Proactive Monitoring |

Continuous Measurement versus Exception-Based Measurement

- Continuous Measurement is focused on monitoring

a system in real time to ensure that it complies with a performance norm (for example, an application server is available for 99.9% of the agreed service hours). The difference between Continuous Measurement and Active Monitoring is that Active Monitoring does not have to be continuous. However, as with Active Monitoring, this is resource intensive and is usually reserved for critical components or services. In most cases the cost of the additional bandwidth and processor power outweighs the benefit of continuous measurement. In these cases monitoring will usually be based on sampling and statistical analysis (e.g. the system performance is reported every 30 seconds and extrapolated to represent overall performance). In these cases, the method of measurement will have to be documented and agreed in the OLAs to ensure that it is adequate to support the Service Reporting Requirements (see Continual Service Improvement publication).

- Exception-Based Measurement does not measure

the real-time performance of a service or system, but detects and reports against exceptions. For example, an event is generated if a transaction does not complete, or if a performance threshold is reached. This is more cost-effective and easier to measure, but could result in longer service outages. Exception-Based Measurement is used for less critical systems or on systems where cost is a major issue. It is also used where IT tools are not able to determine the status or quality of a service (e.g. if printing quality is part of the service specification, the only way to measure this

is physical inspection - often performed by the user rather than IT staff). Where Exception-Based Measurement is used, it is important that both the OLA and the SLA for that service reflect this, as service outages are more likely to occur, and users are often required to report the exception.

Performance Versus Output

There is an important distinction between the reporting used to track the performance of components or teams or department used to deliver a service and the reporting used to demonstrate the achievement of service quality objectives.

IT managers often confuse these by reporting to the business on the performance of their teams or departments (e.g. number of calls taken per Service Desk Analyst), as if that were the same thing as quality of service (e.g. incidents solved within the agreed time).

Performance Monitoring and metrics should be used internally by the Service Management to determine whether people, process and technology are functioning correctly and to standard.

Users and customers would rather see reporting related to the quality and performance of the service.

Although Service Operation is concerned with both types of reporting, the primary concern of this publication is Performance Monitoring, whereas monitoring of Service Quality (or Output-Based Monitoring) will be discussed in detail in the Continual Service Improvement publication.

5.1.2.7 Monitoring in Test Environments

As with any IT Infrastructure, a Test Environment will need to define how it will use monitoring and control. These controls are more fully discussed in the Service Transition publication.

- Monitoring the Test Environment itself: A Test Environment consists of infrastructure, applications and processes that have to be managed and controlled just as any other environment. It is tempting to think that the Test Environment does not need rigorous monitoring and control because it is not a live environment. However, this argument is not valid. If a Test Environment is not properly monitored and controlled, there is a danger of running the tests on equipment that deviates from the standards defined in Service Design.

- Monitoring items being tested: The results of testing have to be accurately tracked and checked. Also it is important that any monitoring tools that have been built into new or changed services have to be tested as well.

5.1.2.8 Reporting And Action

| 'A report alone creates awareness; a report with an action plan achieves results.'

|

Reporting And Dysfunction

Practical experience has shown that there is more reporting in dysfunctional organizations than in effective organizations. This is because reports are not being used to initiate pre-defined action plans, but rather:

to shift the blame for an incident

to try to find out who is responsible for making a decision

as input to creating action plans for future occurrences.

In dysfunctional organizations a lot of reports are produced which no one has the time to look at or query.

|

Monitoring without control is irrelevant and ineffective. Monitoring should always be aimed at ensuring that service and operational objectives are being met. This means that unless there is a clear purpose for monitoring a system or service, it should not be monitored.

This also means that when monitoring is defined, so too should any required actions. For example, being able to detect that a major application has failed is not sufficient.

The relevant Application Management team should also have defined the exact steps that it will take when the application fails.

In addition, it should also be recognized that action may need to be taken by different people, for example a single event (such as an application failure) may trigger action by the Application Management team (to restore service), the users (to initiate manual processing) and management (to determine how this event can be prevented in future).

The implications of this principle are outlined in more detail in relation to Event Management (see section 4.1).

5.1.2.9 Service Operation Audits

Regular audits must be performed on the Service Operation processes and activities to ensure:

- They are being performed as intended

- There is no circumvention

- They are still fit for purpose, or to identify any required changes or improvements.

Service Operation Managers may choose to perform such audits themselves, but ideally some form of independent element to the audits is preferable.

The organization's internal IT audit team or department may be asked to be involved or some organizations may choose to engage third-party consultancy/audit/ assessment companies so that an entirely independent expert view is obtained.

Service Operation audits are part of the ongoing measurement that takes place as part of Continual Service Improvement and are discussed in more detail in that publication.

5.1.2.10 Measurement, Metrics And KPIs

This section has focused primarily on the monitoring and control as a basis for Service Operation. Other sections of the publication have covered some basic metrics that could be used to measure the effectiveness and efficiency of a process.

Although this publication is not primarily about measurement and metrics, it is important that organizations using these guidelines have robust measurement techniques and metrics that support the objectives of their organization. This section is a summary of these concepts.

Measurement

Measurement refers to any technique that is used to evaluate the extent, dimension or capacity of an item in relation to a standard or unit.

- Extent refers to the degree of compliance or completion (e.g. are all changes formally authorized by the appropriate authority)

- Dimension refers to the size of an item, e.g. the number of incidents resolved by the Service Desk

- Capacity refers to the total capability of an item, for example maximum number of standard transactions that can be processed by a server per minute.

|

Measurement only becomes meaningful when it is possible to measure the actual output or dimensions of a system, function or process against a standard or desired level, e.g. the server must be capable of processing a minimum of 100 standard transactions per minute. This needs to be defined in Service Design, and refined over time through Continual Service Improvement, but the measurement itself takes place during Service Operation.

Metrics

| Metrics refer to the quantitative, periodic assessment of a process, system or function, together with the procedures and tools that will be used to make these assessments and the procedures for interpreting them.

|

This definition is important because it not only specifies what needs to be measured, but also how to measure it, what the acceptable range of performance will be and what action will need to be taken as a result of normal performance or an exception. From this, it is clear that any metric given in the previous section of this publication is a very basic one and will need to be applied and expanded within the context of each organization before it can be effective.

Key Performance Indicators

| A KPI refers to a specific, agreed level of performance that will be used to measure the effectiveness of an organization or process.

|

KPIs are unique to each organization and have to be related to specific inputs, outputs and activities. They are not generic or universal and thus have not been included in this publication.

A further reason for not including them is the fact that similar metrics can be used to achieve very different KPIs. For example, one organization used the metric 'Percentage of Incidents resolved by the Service Desk' to evaluate the performance of the Service Desk. This worked effectively for about two years, after which the IT manager began to realize that this KPI was being used to prevent effective Problem Management, i.e. if, after two years, 80% of all incidents are easy enough to be resolved in 10 minutes on the first call, why have we not come up with a solution for them? In effect, the KPI now became a measure for how ineffective the Problem Management teams were.

5.1.2.11 Interfaces To Other Service Lifecycle Practices

Operational Monitoring and Continual Service Improvement

This section has focused on Operational Monitoring and Reporting, but monitoring also forms the starting point for Continual Service Improvement. This is covered in the Continual Service Improvement publication, but key differences are outlined here.

Quality is the key objective of monitoring for Continual Service Improvement (CSI). Monitoring will therefore focus on the effectiveness of a service, process, tool, organization or CI. The emphasis is not on assuring realtime service performance; rather it is on identifying where improvements can be made to the existing level of service, or IT performance.

Monitoring for CSI will therefore tend to focus on detecting exceptions and resolutions. For example, CSI is not as interested in whether an incident was resolved, but whether it was resolved within the agreed time and whether future incidents can be prevented.

CSI is not only interested in exceptions, though. If an SLA is consistently met over time, CSI will also be interested in determining whether that level of performance can be sustained at a lower cost or whether it needs to be upgraded to an even better level of performance. CSI may therefore also need access to regular performance reports.

However, since CSI is unlikely to need, or be able to cope with, the vast quantities of data that are produced by all monitoring activity, they will most likely focus on a specific subset of monitoring at any given time. This could be determined by input from the business or improvements to technology.

.This has two main implications:

- Monitoring for CSI will change over time. They may be interested in monitoring the e-mail service one quarter and then move on to look at HR systems in the next quarter.

- This means that Service Operation and CSI need to build a process which will help them to agree on what areas need to be monitored and for what purpose.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.2 IT Operations

5.2.1 Console Management/Operations Bridge

These provide a central coordination point for managing various classes of events, detecting incidents, managing routine operational activities and reporting on the status or performance of technology components.

Observation and monitoring of the IT Infrastructure can occur from a centralized console - to which all system events are routed. Historically, this involved the monitoring of the master operations console of one or more mainframes - but these days is more likely to involve monitoring of a server farm(s), storage devices, network components, applications, databases, or any other CIs, including any remaining mainframe(s), from a single location, known as the Operations Bridge.

There are two theories about how the Operations Bridge was so named. One is that it resembles the bridge of a large, automated ship (such as spaceships commonly seen in science fiction movies). The other theory is that the Operations Bridge represents a link between the IT Operations teams and the traditional Help Desk. In some organizations this means that the functions of Operational Control and the Help Desk were merged into the Service Desk, which performed both sets of duties in a single physical location.

Regardless of how it was named, an Operations Bridge will pull together all of the critical observation points within the IT Infrastructure so that they can be monitored and managed from a centralised location with minimal effort. The devices being monitored are likely to be physically dispersed and may be located in centralized computer installations or dispersed within the user community, or both.

The Operations Bridge will combine many activities, which might include Console Management, event handling, firstline network management, Job Scheduling and out-of-hours support (covering for the Service Desk and/or

second-line support groups if they do not work 24/7). In some organizations, the Service Desk is part of the Operations Bridge.

The physical location and layout of the Operation's Bridge needs to be carefully designed to give the correct accessibility and visibility of all relevant screens and devices to authorized personnel. However, this will become a very sensitive area where controlled access and tight security will be essential.

Smaller organizations may not have a physical Operations Bridge, but there will certainly still be the need for Console Management, usually combined with other technical roles. For example, a single team of technical staff will manage the network, servers and applications. Part of their role will be to monitor the consoles for those systems - often using virtual consoles so that they can perform the activity from any location. However, it should be noted that these virtual consoles are powerful tools and, if used in insecure locations or over unsecured connections, could represent a significant security threat.

5.2.2 Job Scheduling

IT Operations will perform standard routines, queries or reports delegated to it as part of delivering services; or as part of routine housekeeping delegated by Technical and Application Management teams.

Job Scheduling involves defining and initiating job scheduling software packages to run batch and real-time work. This will normally involve daily, weekly, monthly, annual and ad hoc schedules to meet business needs.

In addition to the initial design, or periodic redesign, of the schedules, there are likely to be frequent amendments or adjustments to make during which job dependencies have to be identified and accommodated. There will also be a role to play in defining alerts and Exception Reports to be used for monitoring/checking job schedules. Change Management plays an important role in assessing and validating major changes to schedules, as well as creating Standard Change procedures for more routine changes.

Run-time parameters and/or files have to be received (or expedited if delayed) and input - and all run-time logs have to be checked and any failures identified.

If failures do occur, then re-runs will have to be initiated, under the guidance of the appropriate business units, often with different parameters or amended data/file versions. This will require careful communications to ensure correct parameters and files are used.

Many organizations are faced with increasing overnight batch schedules which can, if they overrun the overnight batch slot, adversely impact upon the online day services - so are seeking ways of utilizing maximum overnight capacity and performance, in conjunction with Capacity Management. This is where Workload Management techniques can be useful, such as:

- Re-scheduling of work to avoid contention on specific devices or at specific times and improve overall throughput

- Migration of workloads to alternative

- platforms/environments to gain improved performance and/or throughput (virtualization capabilities make this far more achievable by allowing dynamic, automated migration)

- Careful timing and 'interleaving' of jobs to gain maximum utilization of available resources.

Anecdote

One large organization, which was faced with batch overrun/utilization problems, identified that, due to human nature where people were seeking to be 'tidy', all jobs were being started on the hour or at 15-minute intervals during the hour (i.e. n o'clock, 15 minutes past, half past, 15 minutes to, etc.).

By re-scheduling of work so that it started as soon as other work finished, and staggering the start times of other work, it was able to gain significant reductions in contention and achieve much quicker overall processing, which resolved its problems without a need for upgrades.

|

Job Scheduling has become a highly sophisticated activity, including any number of variables - such as timesensitivity, critical and non-critical dependencies, workload balancing, failure and resubmission, etc. As a result, most operations rely on Job Scheduling tools that allow IT Operations to schedule jobs for the optimal use of technology to achieve Service Level Objectives.

The latest generation of scheduling tools allows for a single toolset to schedule and automate technical activities and Service Management process activities (such as Change Scheduling). While this is a good opportunity for improving efficiency, it also represents a greater single point of failure. Organizations using this type of tool therefore still use point solutions as agents and also as a backup in case the main toolset fails.

5.2.3 Backup and Restore

Backup and Restore is essentially a component of good IT Service Continuity Planning. As such, Service Design should ensure that there are solid backup strategies for each service and Service Transition should ensure that these are properly tested.

In addition, regulatory requirements specify that certain types of organization (such as Financial Services or listed companies) must have a formal Backup and Restore strategy in place and that this strategy is executed and audited. The exact requirements will vary from country to country and by industry sector. This should be determined during Service Design and built into the service functionality and documentation.

The only point of taking backups is that they may need to be restored at some point. For this reason it is not as important to define how to back a system up as it is to define what components are at risk and how to effectively mitigate that risk.

There are any number of tools available for Backup and Restore, but it is worth noting that features of storage technologies used for business data are being used for backup/restore (e.g. snapshots). There is therefore an increasing degree of integration between Backup and Restore activities and those of Storage and Archiving (see section 5.6).

5.2.3.1 Backup

The organization's data has to be protected and this will include backup (copying) and storage of data in remote locations where it can be protected - and used should it need to be restored due to loss, corruption or implementation of IT Service Continuity Plans.

An overall backup strategy must be agreed with the business, covering:

- What data has to be backed up and the frequency and intervals to be used.

- How many generations of data have to be retained - this may vary by the type of data being backed up, or what type of file (e.g. data file or application executable).

- The type of backup (full, partial, incremental) and checkpoints to be used.

- The locations to be used for storage (likely to include disaster recovery sites) and rotation schedules.

- Transportation methods (e.g. file transfer via the network, physical transportation on magnetic media).

- Testing/checks to be performed, such as test-reads, test restores, check-sums etc.

- Recovery Point Objective. This describes the point to which data will be restored after recovery of an IT Service. This may involve loss of data. For example, a Recovery Point Objective of one day may be supported by daily backups, and up to 24 hours of data may be lost. Recovery Point Objectives for each IT service should be negotiated, agreed and documented in OLAs, SLAs and UCs.

- Recovery Time Objective. This describes the maximum time allowed for recovery of an IT service following an interruption. The Service Level to be provided may be less than normal Service Level Targets. Recovery Time Objectives for each IT service should be negotiated, agreed and documented in OLAs, SLAs and UCs.

- How to verify that the backups will work if they need to be restored. Even if there are no error codes generated, there may be several reasons why the backup cannot be restored. A good backup strategy and operations procedures will minimize the risk of this happening. Backup procedures should include a verification step to ensure that the backups are complete and that they will work if a restore is needed. Where any backup failures are detected, recovery actions must be initiated.

There is also a need to procure and manage the necessary media (disks, tapes, CDs, etc.) to be used for backups, so that there is no shortage of supply.

Where automated devices are being used, pre-loading of the required media will be needed in advance. When loading and clearing media returned from off-site storage it is important that there is a procedure for verifying that these are the right ones. This will prevent the most recent backup being overwritten with faulty data, and then having no valid data to restore. After successful backups have been taken, the media must be removed for storage.

The actual initiation of the backups might be automated, or carried out from the Operations Bridge.

Some organizations may utilize Operations staff to perform the physical transportation and racking of backup copies to/from remote locations, where in other cases this may be handed over to other groups such as internal security staff or external contractors.

If backups are being automated or performed remotely, then Event Monitoring capabilities should be considered so that any failures can be detected early and rectified before they cause problems. In such cases IT Operations has a role to play in defining alerts and escalation paths.

In all cases, IT Operations staff must be trained in backup (and restore) procedures - which must be well documented in the organization's IT Operations Procedures Manual. Any specific requirements or targets should be referenced in OLAs or UCs where appropriate, while any user or customer requirements or activity shoe be specified in the appropriate SLA.

5.2.3.2 Restore

A restore can be initiated from a number of sources, ranging from an event that indicates data corruption, through to a Service Request from a user or customer logged at the Service Desk. A restore may be needed in the case of:

- Corrupt data

- Lost data

- Disaster recovery/IT Service Continuity situation

- Historical data required for forensic investigation.

The steps to be taken will include:

- Location of the appropriate data/media

- Transportation or transfer back to the physical recover location

- Agreement on the checkpoint recovery point and the specific location for the recovered data (disk, directory folder etc)

- Actual restoration of the file/data (copy-back and any roll-back/roll-forward needed to arrive at the agreed checkpoint

- Checking to ensure successful completion of the restore - with further recovery action if needed until success has been achieved.

- User/customer sign-off.

5.2.4 Print and Output

Many services consist of generating and delivering information in printed or electronic form. Ensuring the right information gets to the right people, with full integrity, requires formal control and management.

Print (physical) and Output (electronic) facilities and services need to be formally managed because:

- They often represent the tangible output of a service. The ability to measure that this output has reached the appropriate destination is therefore very important (e.g. checking whether files with financial transaction data have actually reached a bank through an FTP service)

- Physical and electronic output often contains sensitive: or confidential information. It is vital that the appropriate levels of security are applied to both the generation and the delivery of this output.

Many organizations will have centralized bulk printing requirements which IT Operations must handle. In addition to the physical loading and re-loading of paper and the operation and care of the printers, other activities may be needed, such as:

- Agreement and setting of pre-notification of large print runs and alerts to prevent excessive printing by rogue print jobs

- Physical control of high-value stationery such as company cheques or certificates, etc.

- Management of the physical and electronic storage required to generate the output. In many cases IT will be expected to provide archives for the printed and electronic materials

- Control of all printed material so as to adhere to data protection legislation and regulation e.g. HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) in the USA, or FSA (Financial Services Authority) in the UK.

- Where print and output services are delivered directly to the users, it is important that the responsibility for maintaining the printers or storage devices is clearly defined. For example, most users assume that cleaning and maintenance of printers must be performed by IT. If this is not the case, this must be clearly stated in the SLA.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.3 Mainframe Management

Mainframes are still widely in use and have well established and mature practices. Mainframes form the central component of many services and its performance will therefore set a baseline for service performance and user or customer expectations, although they may never know that they are using the mainframe.

The ways in which mainframe management teams are organized are quite diverse. In some organizations Mainframe Management is a single, highly specialized team that manages all aspects from daily operations through to system engineering. In other organizations, the activities are performed by several teams or departments, with engineering and third-level support being provided by one team and daily operations being combined with the rest of IT Operations (and very probably managed through the Operations Bridge).

Typically, the following activities are likely to be undertaken:

- Mainframe operating system maintenance and support

- Third-level support for any mainframe-related incidents/problems

- Writing job scripts

- System programming

- Interfacing to hardware (H/W) support; arranging maintenance, agreeing slots, identifying H/W failure, liaison with H/W engineering.

- Provision of information and assistance to Capacity Management to help achieve optimum throughput, utilization and performance from the mainframe.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.4 Server Management And Support

Servers are used in most organizations to provide flexible and accessible services from hosting applications or databases, running client/server services, Storage, Print and File Management. Successful management of servers is therefore essential for successful Service Operation.

The procedures and activities which must be undertaken by the Server Team(s) or department(s) - separate teams may be needed where different server-types are used (UNIX, Wintel etc) - include:

- Operating system support: Support and maintenance of the appropriate operating system(s) and related utility software (e.g. fail-over software) including patch management and involvement in defining backup and restore policies.

- Licence management for all server CIs, especially operating systems, utilities and any application software not managed by the Application Management teams.

- Third-level support: Third-level support for all server and/or server operating system-related incidents, including diagnosis and restoration activities. This will also include liaison with third-party hardware support contractors and/or manufacturers as needed to escalate hardware-related incidents.

- Procurement advice: Advice and guidance to the business on the selection, sizing, procurement and usage of servers and related utility software to meet business needs.

- System security: Control and maintenance of the access controls and permissions within the relevant server environment(s) as well as appropriate system and physical security measures. These include identification and application of security patches, Access Management (see section 4.5) and intrusion detection.

- Definition and management of virtual servers. This implies that any server that has been designed and built around a common standard can be used to process workloads from a range of applications or users. Server Management will be required to set these standards and then ensure that workloads are appropriately balanced and distributed. They are also responsible for being able to track which workload is being processed by which server so that they are able to deal with incidents effectively.

- Capacity and Performance: Provide information and assistance to Capacity Management to help achieve optimum throughput, utilization and performance from the available servers. This is discussed in more detail in Service Design, but includes providing guidance on, and installation and operation of, virtualization software so as to achieve value for money by obtaining the highest levels of performance and utilization from the minimal number of servers.

- Other routine activities include:

- Defining standard builds for servers as part of the provisioning process. This is covered in more detail in Service Design and Service Transition

- Building and installing new servers as part of ongoing maintenance or for the provision of new services. This is discussed in more detail in Service Transition

- Setting up and managing clusters, which are aimed at building redundancy, improving service performance and making the infrastructure easier to manage.

- Ongoing maintenance. This typically consists of replacing servers or 'blades' on a rolling schedule to ensure that equipment is replaced before it fails or becomes obsolete. This results in servers that are not only fully functional, but also capable of supporting evolving services.

- Decommissioning and disposal of old server equipment. This is often done in conjunction with the organization's environmental policies for disposal.

5.5 Network Management

As most IT services are dependent on connectivity, Network Management will be essential to deliver services and also to enable Service Operation staff to access and manage key service components.

Network Management will have overall responsibility for all of the organization's own Local Area Networks (LANs), Metropolitan Area Networks (MANs) and Wide Area Networks (WANs) - and will also be responsible for liaising with third-party network suppliers.

Note on managing VoIP as a service

Many organizations have experienced performance and availability problems with their VoIP solutions, in spite of the fact that there seems to be more than adequate bandwidth available. This results in dropped calls and poor sound quality. This is usually because of variations in bandwidth utilization during the call, which is often the result of utilization of the network by other users, applications or other web activity. This

has led to the differentiation between measuring the bandwidth available to initiate a call (Service Access Bandwidth - or SAB) and the amount of bandwidth that must be continuously available during the call (Service Utilization Bandwidth - or SUB). Care should be taken in differentiating between these when

designing, managing or measuring VoIP services.

|

Their role will include the following activities:

- Initial planning and installation of new networks/network components; maintenance and upgrades to the physical network infrastructure. This is done through Service Design and Service Transition.

- Third-level support for all network related activities, including investigation of network issues (e.g. pinging or trace route and/or use of network management software tools - although it should be noted that pinging a server does not necessarily mean that the service is available!) and liaison with third-parties as necessary. This also includes the installation and use of 'sniffer' tools, which analyse network traffic, to assist in incident and problem resolution.

- Maintenance and support of network operating system and middleware software including patch management, upgrades, etc.

- Monitoring of network traffic to identify failures or to spot potential performance or bottleneck issues.

- Reconfiguring or rerouting of traffic to achieve improved throughput or batter balance - definition of rules for dynamic balancing/routing.

- Network security (in liaison with the organization's Information Security Management) including firewall management, access rights, password protection etc.

- Assigning and managing IP addresses, Domain Name Systems (DNSs - which convert the name of a service to its associated IP address) and Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) systems, which enable access and use of the DNS.

- Managing Internet Service Providers (ISPs).

- Implementing, monitoring and maintaining Intrusion Detection Systems on behalf of Information Security Management. They will also be responsible for ensuring that there is no denial of service to legitimate users of the network.

- Updating Configuration Management as necessary by documenting CIs, status, relationships, etc.

Network Management is also often responsible, often in conjunction with Desktop Support, for remote connectivity issues such as dial-in, dial-back and VPN facilities provided to home-workers, remote workers or suppliers.

Some Network Management teams or departments will also have responsibility for voice/telephony, including the provision and support for exchanges, lines, ACD, statistical software packages etc. and for Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) and Remote Monitoring (RMon) systems.

At the same time, many organizations see VoIP and telephony as specialized areas and have teams dedicated to managing this technology. Their activities will be similar to those described above.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.6 Storage And Archive

Many services require the storage of data for a specific time and also for that data to be available off-line for a certain period after it is no longer used. This is often due to regulatory or legislative requirements, but also because history and audit data are invaluable for a variety of purposes, including marketing, product development, forensic investigations, etc.

A separate team or department may be needed to manage the organization's data storage technology such as:

- Storage devices, such as disks, controllers, tapes, etc.

- Network Attached Storage (NAS), which is storage attached to a network and accessible by several clients

- Storage Area Networks (SANs) designed to attach computer storage devices such as disk array controllers and tape libraries. In addition to storage devices, a SAN will also require the management of several network components, such as hubs, cables, etc.

- Direct Attached Storage (DAS), which is a storage device directly attached to a server

- Content Addressable Storage (CAS) which is storage that is based on retrieving information based on its content rather than location. The focus in this type of system is on understanding the nature of the data and information stored, rather than on providing specific storage locations.

Regardless of what type of storage systems are being

used, Storage and Archiving will require the management of the infrastructure components as well as the policies related to where data is stored, for how long, in what form

and who may access it. Specific responsibilities will include:

- Definition of data storage policies and procedures

- File storage naming conventions, hierarchy and

placement decisions

- Design, sizing, selection, procurement, configuration

and operation of all data storage infrastructure

- Maintenance and support for all utility and

middleware data-storage software

- Liaison with Information Lifecycle Management

team(s) or Governance teams to ensure compliance

with freedom of information, data protection and IT

governance regulations

- Involvement with definition and agreement of

archiving policy

- Housekeeping of all data storage facilities

- Archiving data according to rules and schedules defined during Service Design. The Storage teams or departments will also provide input into the definition of these rules and will provide reports on their effectiveness as input into future design

- Retrieval of archived data as needed (e.g. for audit purposes, for forensic evidence, or to meet any other business requirements)

- Third-line support for storage- and archive-related incidents.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.7 Database Administration

Database Administration must work closely with key Application Management teams or departments - and in some organizations the functions may be combined or linked under a single management structure. Organizational options include:

- Database administration being performed by each Application Management team for all the applications under its control

- A dedicated department, which manages all databases, regardless of type or application

- Several departments, each managing one type of database, regardless of what application they are part of.

Database Administration works to ensure the optimal performance, security and functionality of databases that they manage. Database Administrators typically have the following responsibilities:

- Creation and maintenance of database standards and policies

- Initial database design, creation, testing

- Management of the database availability and performance; resilience, sizing, capacity volumetrics etc.

- Resilience may require database replication, which would be the responsibility of Database Administration

- Ongoing administration of database objects: indexes, tables, views, constraints, sequences snapshots and stored procedures; page locks - to achieve optimum utilization

- The definition of triggers that will generate events, which in turn will alert database administrators of potential performance or integrity issues with the database

- Performing database housekeeping - the routine tasks that ensure that the databases are functioning optimally and securely, e.g. tuning, indexing, etc.

- Monitoring of usage; transaction volumes, response times, concurrency levels, etc.

- Generating reports. These could be reports based on the data in the database, or reports related to the performance and integrity of the database

- Identification, reporting and management of database security issues; audit trails and forensics

- Assistance in designing database backup, archiving and storage strategy

- Assistance in designing database alerts and event management

- Provision of third-level support for all database-related incidents.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.8 Directory Services Management

A Directory Service is a specialized software application that manages information about the resources available on a network and which users have access to. It is the basis for providing access to those resources and for ensuring that unauthorized access is detected and prevented (see section 4.5 for detailed information on Access Management).

Directory Services views each resource as an object of the Directory Server and assigns it a name. Each name is linked to the resource's network address, so that users don't have to memorize confusing and complex addresses.

Directory Services is based on the OSI's X.500 standards and commonly uses protocols such as Directory Access Protocol (DAP) or Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP). LDAP is used to support user credentials for application login and often includes internal and external user/customer data which is especially good for extranet call logging. Since LDAP is a critical operational tool, and generally kept up to date, it is also a good source of data and verification for the CMS.

Directory Services Management refers to the process that is used to manage Directory Services. Its activities include:

- Working as part of Service Design and Service Transition to ensure that new services are accessible and controlled when they are deployed

- Locating resources on a network (if these have not already been defined during Service Design)

- Tracking the status of those resources and providing the ability to manage those resources remotely

- Managing the rights of specific users or groups of users to access resources on a network

- Defining and maintaining naming conventions to be used for resources on a network

- Ensuring consistency of naming and access control on different networks in the organization

- Linking different Directory Services throughout the organization to form a distributed Directory Service, i.e. users will only see one logical set of network resources. This is called Distribution of Directory Services

- Monitoring Events on the Directory Services, such as unsuccessful attempts to access a resource, and taking the appropriate action where required

- Maintaining and updating the tools used to manage Directory Services.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.9 Desktop Support

As most users access IT services using desktop or laptop computers, it is key that these are supported to ensure the agreed levels of availability and performance of services.

Desktop Support will have overall responsibility for all of the organization's desktop and laptop computer hardware, software and peripherals. Specific responsibilities will include:

- Desktop policies and procedures, for example licensing policies, use of laptops or desktops for personal purposes, USB lockdown, etc.

- Designing and agreeing standard desktop images

- Desktop service maintenance including deployment of releases, upgrades, patches and hot-fixes (in conjunction with Release Management (see Service Transition publication for further details)

- Design and implementation of desktop archiving/rebuild policy (including policy relating to cookies, favourites, templates, personal data, etc.)

- Third-level support of desktop-related incidents, including desk-side visits where necessary

- Support for connectivity issues (in conjunction with Network Management) to home-workers, mobile staff, etc.

- Configuration control and audit of all desktop equipment (in conjunction with Configuration Management and IT Audit).

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.10 Middleware Management

Middleware is software that connects or integrates

software components across distributed or disparate applications and systems. Middleware enables the effective transfer of data between applications, and is therefore key to services that are dependent on multiple applications or data sources.

A variety of technologies are currently used to support program-to-program communication, such as object request brokers, message-oriented middleware, remote procedure calls and point-to-point web services. Newer technologies are emerging all the time, for example Enterprise Service Bus (ESB), which enables programs, systems and services to communicate with each other regardless of the architecture and origin of the applications. This is especially being used in the context of deploying Service Oriented Architectures (SOAs).

Middleware Management can be performed as part of an Application Management function (where it is dedicated to a specific application) or as part of a Technical Management function (where it is viewed as an extension to the Operating System of a specific platform).

Functionality provided by middleware includes:

- Providing transfer mechanisms for data from various applications or data sources

- Sending work to another application or procedure for processing

- Transmitting data or information to other systems, such as sourcing data for publication on websites (e.g. publishing Incident status information)

- Releasing updated software modules across distributed environments

- Collation and distribution of system messages and instructions, for example Events or operational scripts that need to be run on remote devices

- Multicast setup with networks. Multicast is the delivery of information to a group of destinations simultaneously using the most efficient delivery route

- Managing queue sizes.

Middleware Management is the set of activities that are used to manage middleware. These include:

- Working as part of Service Design and Transition to ensure that the appropriate middleware solutions are chosen and that they can perform optimally when they are deployed

- Ensuring the correct operation of middleware through monitoring and control

- Detecting and resolving Incidents related to middleware

- Maintaining and updating middleware, including licensing, and installing new versions

- Defining and maintaining information about how applications are linked through Middleware. This should be part of the CMS (see Service Transition publication).

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.11 Internet/Web Management

Many organizations conduct much of their business through the Internet and are therefore heavily dependent upon the availability and performance of their websites. In such cases a separate Internet/Web Support team or department will be desirable and justified.

The responsibilities of such a team or department incorporate both Intranet and Internet and are likely to include:

- Defining architectures for Internet and web services

- The specification of standards for development and management of web-based applications, content, websites and web pages. This will typically be done during Service Design

- Design, testing, implementation and maintenance of websites. This will include the architecture of websites and the mapping of content to be made available

- In many organizations, web management will include the editing of content to be posted onto the web

- Maintenance of all web development and management applications

- Liaison and advice to web-content teams within the business. Content may reside in applications or storage devices, which implies close liaison with Application Management and other Technical Management teams

- Liaison with and supplier management of ISPs, hosts, third-party monitoring or virtualization organizations etc. In many organizations the ISPs are managed as part of Network Management

- Third-level support for Internet-/web-related incidents

- Support for interfaces with back-end and legacy systems. This will often mean working with members of the Application Development and Management teams to ensure secure access and consistency of functionality

- Monitoring and management of website performance and including: heartbeat testing, user experience simulation, benchmarking, on-demand load balancing, virtualization

- Website availability, resilience and security. This will form part of the overall Information Security Management of the organization.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

5.12 Facilities and Data Centre Management

Facilities Management refers to the management of the physical environment of IT Operations, usually located in Data Centres or computer rooms. This is a vast and complex area and this publication will provide an overview of its key role and activities. A more detailed overview is contained in Appendix E.

In many respects Facilities Management could be viewed as a function in its own right. However, because this publication is focused on where IT Operations are housed, it will cover Facilities Management specifically as it relates to the management of Data Centres and as a subset of the IT Operations Management function.

Important note regarding Data Centres

Data Centres are generally specialized facilities and, while they use and benefit from generic Facilities Management disciplines, they need to adapt these. For example layout, heating and conditioning, power planning and many other aspects are all managed uniquely in Data Centres.